Hands, flowers, fruit

Hand 1, Edward John Poynter 1836–1919, Helen, 1881

Hand 2, Charles Landelle 1821–1908, Isménie, nymph of Diana, 1878

Flowers, William Buelow Gould 1827–1853, Flowers and fruit, 1849

Fruit, John Everett Millais 1829–1896, The captive, 1882

x

Please disturb

Graeme Smith: Thomas Demand, The Dailies, with contributions by Louis Begley and Miuccia Prada, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Commercial Travellers’ Association (CTA), MLC Centre, Martin Place, Sydney, March 23-April 22.

For better exhibition photography than mine please visit RealTime 109, June 2012.

Observation

When Sydney people walk into an unfamiliar room the first thing they do is head for the window. Everything—including the art on the walls—is sized up only after a quick assessment of the quality of the view. Sydney is a view city—even beyond white yachts bobbing on a sparkling harbour.

The ‘Rear Window’ effect of looking into the rooms of others, the lovely mute blankness of windowless brick, a neighbour’s frangipani or the shiny seduction of a retail strip all make good views, as they would in other cities, but in Sydney it’s more important. The view reigns. Sydney seems to look outwards; looking inwards is inappropriate behaviour. Disturbing. As is randomly opening the door to a hotel room you haven’t booked.

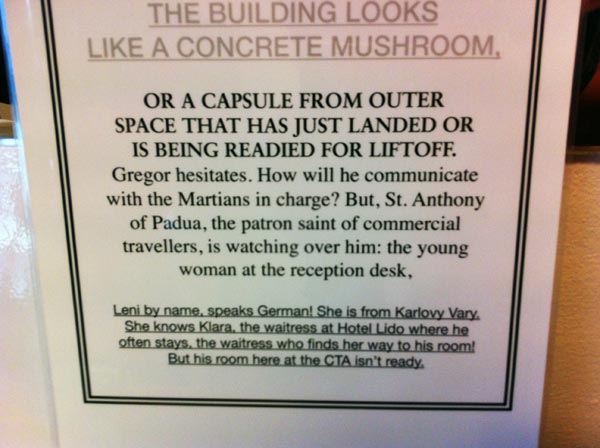

The Commercial Travellers’ Association houses a little-known, little hotel—a mid-70s Harry Seidler designed concrete mushroom in the centre of Sydney’s financial district. On one of the above ground floors, 16 little bedrooms look out radially onto the high-end retail and grand bank facades of Castlereagh Street and Martin Place. This was the setting for German artist Thomas Demand’s, The Dailies, and where a polite attendant in black invited me to start anywhere—so I opened the door to room 413 and went to the window.

Through the window

Prada, in an Art Deco building, Martin Place.

On the wall

A photograph of a window in a brown wall. The window has a cheap-looking venetian blind covering it. The lower third of the slats is dishevelled—a word normally used for hair or clothing that also works for mussed up venetians. The ceiling is standard office-commercial. Cheap. Utilitarian. All of the above is meticulously constructed from paper, photographed, then beautifully and expensively printed using an almost obsolete process called dye transfer, by Thomas Demand. The result is a slickly real image that doesn’t quite add up.

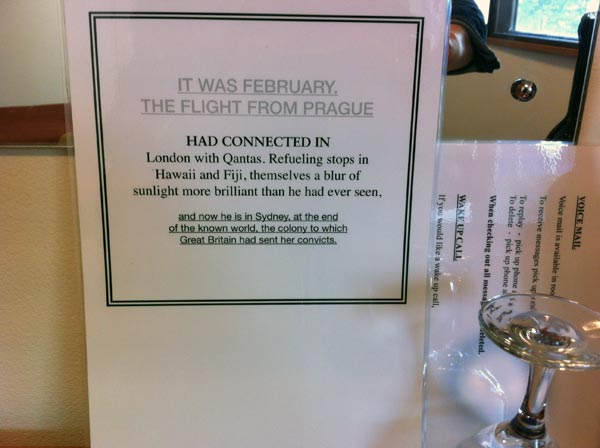

On the dresser

A tiny electric jug (everything is tiny in these rooms), a little telephone, a small bottle of wine, one glass, a laminated sheet of house information that ends predictably with…

“THIS IS A NON SMOKING ROOM

THANK YOU’

and laminated in the same hotel-room manner, a story fragment by American novelist Louis Begley…

“THE WHITE CORRIDOR WHEN

THEY ARRIVED AT

GREGOR’S FLOOR

MAKES HIM THINK OF A HOSPITAL.

HE TELLS THAT TO LENI.

She explodes in laughter and explains

how on every floor the corridor circles the building.

On some floors there are only double rooms.

This is the floor of singles.”

In the air

A fragrance designed or specified (not sure) by Miuccia Prada.

The Dailies

One circular floor, level four. Sixteen rooms. Fifteen, each with a photograph, a fragrance, a view and a fragment of story about Gregor the commercial traveller and Leni the receptionist. One room is locked, a red swing tag on the handle reading, “Please do not disturb.”

Begin

Turn the handle and push against one of the tightly sprung doors; so tightly sprung that it feels locked, until the attendant in black tells you to push a bit harder. A touch of guilt about randomly barging into a hotel room that isn’t yours, then a hint of relief in discovering that no one is there. The lunchtime city outside is soundless through the double glazing. The only sound in the room is the humming of the air conditioner through the grate in the bulkhead, sounding for a moment like a shower running in the room next door. Look at the photograph on the wall above the bed. Read the text on the dresser. Look out the window. Step back (not far in this tiny room) and frame all three—the picture, the dresser with the text, the window—in your field of vision. Turn back to the door. Turn the handle, open, realise it’s the door for the bathroom, and a slight sense of disorientation sets in.

Few of us miss this point, that regardless of where you are in the world, these mean little hotel rooms, apart from all looking the same, have one other thing in common: they’re non-places. Places between other places. In The Dailies, Demand’s photographs pick up on this and push the fourth floor into another level of disengagement.

Loaded emptiness

Demand has described his subjects as simply places you pass by, things that are formally interesting (no more than that), revisited memories fixed in photography or the nuclei of narratives. The refreshingly non-interpretive John Kaldor calls them little observations in the city, and this is essentially what they are. But it’s the effect of moving through the gaps, being in-between these little stories, that draws you in to another, less worldly place. A description I once heard used for the loaded emptinesses of Berlin comes to mind and seems to fit the feeling perfectly: ghostly present absences; and picking up on the theme I did find myself doing this door-to-door visitation a bit like a commercial travelling wraith. Cut off, removed, silenced, disconnected—but at the same time hoping that the group of jabbering school kids I saw earlier had finally pissed off and left me to wander alone—to be trapped in the gaps between someone else’s story, each door opening to reveal just a sampling of what wasn’t there.

Give and take

Begley was delightful. His words played with me—and the building, and Sydney, and Australia, and readers, and Kafka, and airports, and commercial travellers and lousy little hotel rooms. Regretfully, Prada’s fragrances didn’t do a thing—but only because of the limiting effects of asthma and a cold. On the other hand, Thomas Demand seemed to be provoking a type of reflection, and presumably insight, that only comes about through displacement. Demand gives, prescribing the vision, as he says, and Demand takes, handing you the moment and at the same time cutting it away. The subject in the photograph is a construction. It has an aura of reality but at the same time it doesn’t add up. It’s the slightly disturbing, preternatural silence of the spaces that exist either side of these disconnected moments that I find overwhelmingly seductive.

Graeme Smith, RealTime 109, June July 2012

Poetic objects

Part of an interview with the artist, Maria Volokhova, Berlin, September 2011.

Graeme Smith:

Your introduction in Poetry Happens [exhibition, Berlin, June 2011] talks about this new level of emotional interaction between the object and the user. And I guess one of the ways I think about it is that these are rituals of engagement. What I’m interested in is how these interactions happen. It’s not a simple experience, it’s complex. And it’s not just about the experience of the user, there’s something more there and the closest I can get to it is that it’s like a form of possession or maybe a fascination with the unfamiliar, in that some objects have a sense of mystery—the attraction being that you don’t understand them. I think what I found with your work is that I could enjoy it without interpretation. Or be suspended between interpretations. What I’m fishing for is an explanation from you about how you feel about the work and how you think it affects other people. It may have something to do with materials. It may have something to do with your graphics background. Or alternatively I’m asking, ‘What is a poetic object?’

Maria Volokhova:

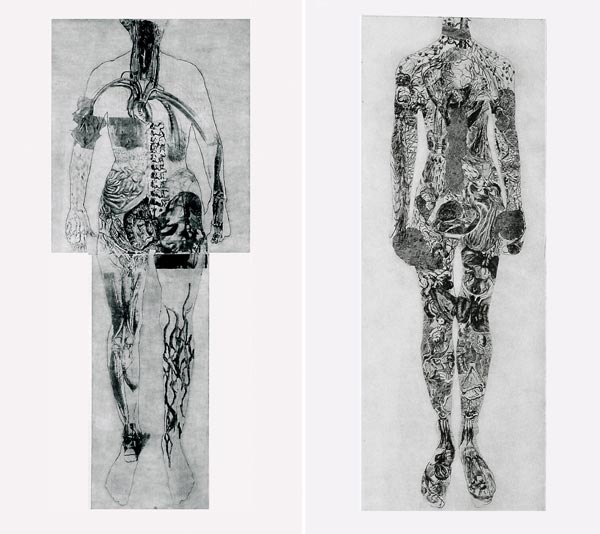

For me, it’s just something I’m doing every day. I came to porcelain a different way to other ceramic artists. [From image-making.] They studied ceramics and are looking for what they can do with ceramics. My approach was different. I chose the material to express my thoughts. I’m working with this idea of inner organs and inner life. It’s not about the organs actually, it’s more this psychological way of thinking about people. I try to confront people with this idea and the thing with graphics [I produced before this] is that sometimes the work looked too expressive because it was black and white and people were shocked because it’s too open with all these organs… so they were just shocked.

This is how the Dolci Lacrime project started. The name comes from this music from 18th century Venice. For this series you can recognise that it’s a useable object, say a teapot.

It’s a teapot first—but it doesn’t look like a normal teapot, so you start to think , ‘Why?’ To think about it in terms of an idea. So first of all if I’m doing something with porcelain it should be functional. But even if it’s functional they won’t use it automatically. They have to think about how to use it so it’s something which gives rise to ideas. New thoughts.

But also, I just like the shapes of organs; maybe that’s why my work is getting more poetic.

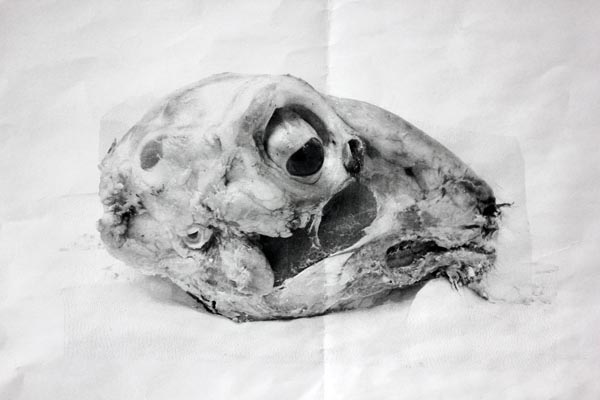

(Refers to a picture of a flayed sheeps head).

When I saw the sheep’s head I was fascinated by it. I didn’t plan to do a project with sheep heads and I wasn’t looking for one. One day I was just buying stuff for another project and when I saw it I thought, ‘Ok. I have to buy it now. I brought it back to the studio and the idea was to start working with it the next day. But instead I just started to make a mould from it immediately. Only later, I connected it to Murakami’s Wild Sheep Chase. It really took me.’

GS:

Why did it take you?

MV:

I don’t know. That’s why I later connected it with Wild Sheep Chase. Murakami tells a story about this Mongolian legend in which there’s one sheep with a star on it’s side. The sheep chooses someone and gives his soul to that person and they become wealthy and have everything they need until the sheep decides to get out. I started thinking about what Murakami may be saying. I think maybe he’s criticising aspects of Japanese communal behaviour? I lived for quite some time in Japan. Then I thought about the sheep as a bringer of luck…but also, I just like how the head looks. For me it’s beautiful. Sometimes when I’m showing I hear people saying things like, Oh it’s so ugly’, and I could work on it and make it all smooth, glossy, all beautiful but I decided to leave it all in, to make it realistic, the teeth and so on, to leave it like it is. Finally, I like how all these organs look. I have a different aesthetic.

GS:

I think I’m still asking what makes a poetic object. Avoiding ‘inspiration’ as a source. It’s always easy for people to talk about inspiration. It’s more than being inspired by something and expressing it, it’s also about making an emotion (not just expressing one). Is that what happens?

MV:

Yes, I want to awake an emotion in a viewer. Not just passive.

GS:

That’s where I think that slight confrontation comes in. Not that you’re necessarily consciously engineering it to upset someone…or maybe you are?

MV:

It’s not really about shocking. Like I was saying about the sheeps head, I’m not expecting a shock. I think it’s a nice object.

GS:

You said you lived in Tokyo for some time. It’s sort of natural to start making comparisons between cities you’ve experienced. There’s the everyday stuff, like both cities have lots of bikes and crows. But apart from this I’m always interested in the slow aspects of a city and the fast aspects. I came here ready to ask Berlin people, ‘Is this a slow city or a fast city?’, and I’ve realised that it’s a dumb question because like Tokyo, it’s both.

MV:

It’s both because it’s a relaxed city but it’s fast. Nobody has time. But for me, I like big cities, I like it fast. It’s not so fast as Moscow. I just came back from there. I could compare Moscow to Tokyo. It’s crowded and crazy. Regimented. They don’t have time for anything.

GS:

I was wondering whether a poetic object (forgive me for dwelling on poetic) is something that slows you down? Makes you contemplate and think? Is that also what a poetic object is? I could go to a large department store, buy some Prada, take it home, look at it and go wow, great, then that’s it. It’s over. But with an artwork, someone buys one of your objects and they don’t always get it. Or at least they don’t need to. There’s a mystery within it. Also, even though you don’t engineer them, there are aspects I suspect in the viscera, organs, veins, skulls, whatever that suggest death, and in big cities people—I think—people are all running around trying to forget about death. I’m wondering if there are aspects in your choice of subject that slow down someone’s experience, and that also makes for a poetic object?

MV:

It was never my idea to go about making poetic objects. This is how other people see it. My idea is that someone just doesn’t use the object but sits down and thinks about it. I like it when they can discover new details in it, find new experiences.

GS:

My understanding of what you’re saying is that slowly, someone gets other things from it. Other things seep into their head, and that happens over time. Time is important. You can look at some objects and it’s over after the first viewing whereas you can look at one of these objects and it has a longevity because it will never be completely interpreted. And this is good.

I’m also interested in how it happens, how you work with the materials and why you’re attracted to certain materials.

MV:

I’m working with porcelain right now because it’s expressive in a good way. It’s really fine. I also like graphics. I would like to go back to print making as well. I have ideas and I just look for the best tools to express them. This is how I came to porcelain. Although I don’t want to jump around too much I’d like to go back to print making again but right now I don’t have time. I also like to research. Things get boring somehow. I need time for things. I know I can never complete a project in one month. When I start doing something I know that the first two or three trials could be really bad and nothing will happen but for me I just know that I have to work on it more and more. This is how I get a result finally. Now I know how it happens. I can never sit at a table and say I’ll do this, then this… I know some people work this way. They can go to their studio and know exactly what they’re going to do. For me, it’s different. I have an idea and I think I know exactly what I’ll do then I start to work on it and see that I don’t know anything.

GS:

Tell me about your current project.

MV:

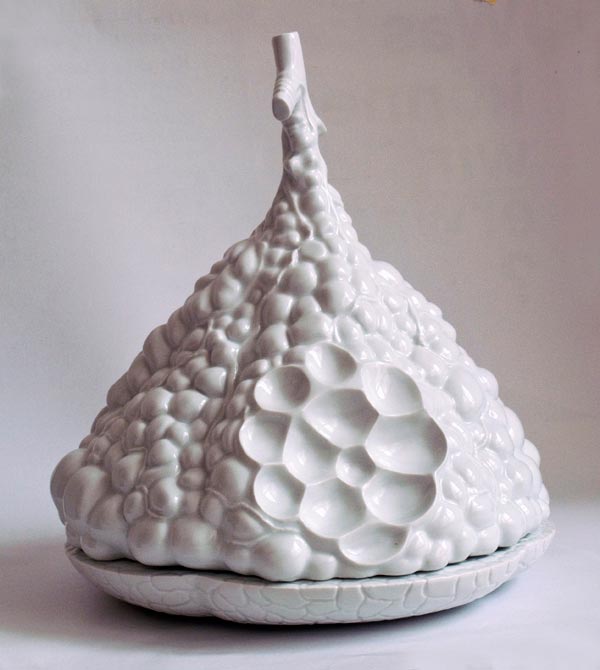

My big project now is this one.

[Large vessel in the shape of a lung.]

It’s a mould now. A huge one.

GS:

Is this another functioning object?

MV:

Yes. This is just the upper part, the lid for a bowl for some kind of warm food. It takes a lot of time. It’s all modelled by hand. Now I’ll slipcast it and fire it and see how it comes out in porcelain because porcelain is a difficult material.

GS:

Is this what you learnt in Tokyo?

MV:

I learnt this technique in Germany. Slipcasting is a European technique. I didn’t learn traditional Japanese techniques but I wanted to see how they work with porcelain and I learnt a lot of technical things. In Tokyo they really control the kilns and they know how porcelain reacts. This was good for me because my shapes are very difficult for porcelain. With my teapot most people told me you’ll never get those shapes in porcelain. They said, ‘Nobody works like you are working in porcelain. You’ll never be able to fire it.’ But I wanted it to be produced with an industrial finish: a nice perfect surface.

GS:

I met another artist a few days ago who said that the energy is here in Berlin but not the money. Most of his collectors are not from Berlin.

MV:

From an economic aspect most of the designers and artists who are living in Berlin are usually more active outside of Berlin than in Berlin. Berlin is a cheap city but a poor city.

GS:

Poor but sexy. Isn’t that what Wowi* says?

MV:

Everyone says it. Berlin looks nice and it’s relaxed here but it’s a poor city.

*

Nickname for Klaus Wowereit, Mayor of Berlin

The Dailies

The Dailies

Thomas Demand

Commercial Travellers’ Association club, Martin Place, Sydney.

22 March – 22 April 2012.

x

Back to Sydney

Coming back to Sydney from Berlin I rediscovered a place full of colour.

Some weaving from Happy Talk House.

Happy Talk House.

B’s new look.

Janet Echelman’s aerial net installation, Tsunami 1.26.

Last of the camellias at Double Bay.

Atak revisited, Berlin

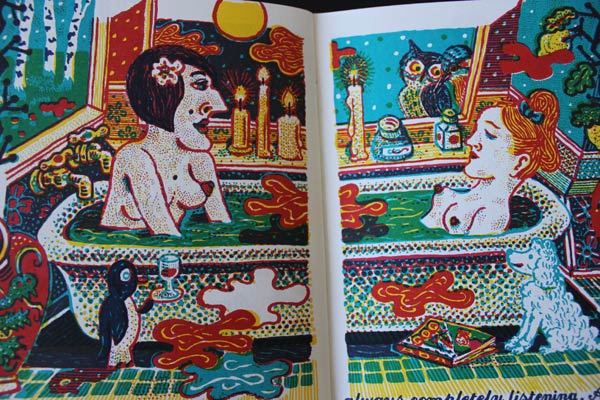

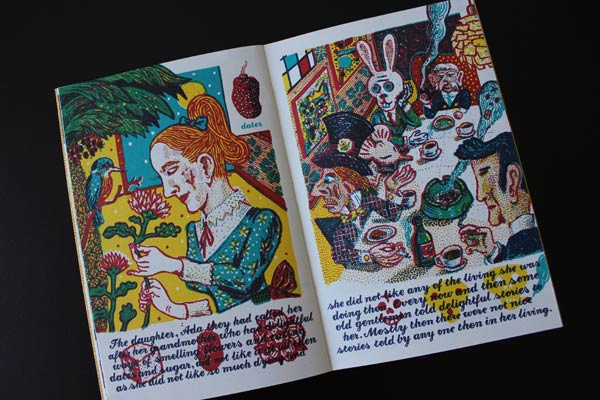

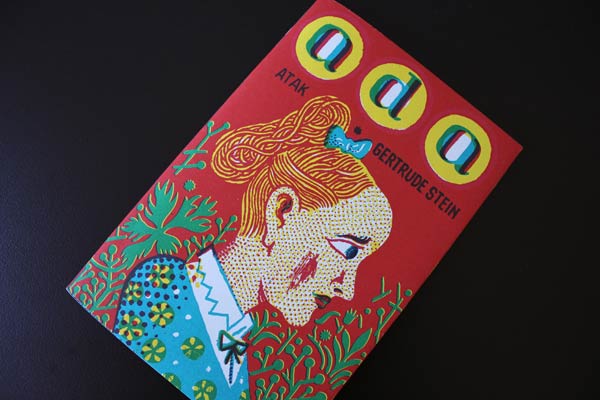

Ada. Gertrude Stein’s word portrait of Alice B Toklas. Hand separated artworks by Atak.

Publisher: Nobrow, London.

Next:

Work in progress for The Mysterious Stranger by Mark Twain.

Volokhova studio revisited, Berlin

Some finished pieces in a series called Dolci Lacrime.

x

Working on a new piece.

Mould for the top section.

Making the mould for the ‘handle’.

x

Flying gardens, Berlin

Cloud Cities, Tomas Saraceno, Hamburger Bahnhof Museum, 15 September 2011 – 15 January 2012.

As evocative as this vision of the future is, another exhibition at Hamburger Bahnhof—from the past—comes closer to my heart: the mainly early 70s video art from the Mike Steiner Collection called Live to Tape. There’s the totally engrossing documentation of an art theft, There is a Criminal Touch to Art, 1976, and, Made in New York, 1973, a hilarious film about catching alligators in New York’s sewers.

x