Works: written (the other life of objects)

The Other Life of Objects is taken from Undefinable Places In-between — a series of short essays I have written and continue to write under that title.

The Other Life of Objects

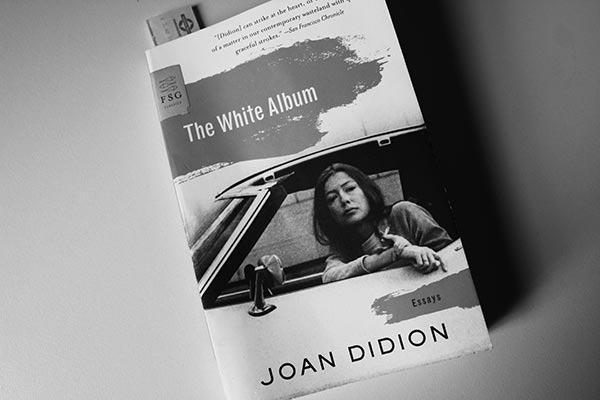

I have just finished reading The White Album — a book of mainly 70s essays by the US writer Joan Didion — and I’m feeling inadequate, or more to the point, pointless. Didion seems to get to her own point by the sparest means, and with language that is, as The New York Times Book Review says, “subtly musical in its phrasing and exact”.

In one essay, At the Dam, she recounts a second visit to the Hoover Dam where her guide from the Bureau of Reclamation invites her to touch one of the turbines.

We watched a hundred-ton steel shaft plunging down to that place where the water was. And finally we got down to that place where the water was, where the water sucked out of Lake Mead roared through thirty-foot penstocks and then into thirteen-foot penstocks and finally into the turbines themselves. “Touch it,” the Reclamation said, and I did, and for a long time I just stood there with my hands on the turbine. It was a peculiar moment, but so explicit as to suggest nothing beyond itself.*

Didion became fixated on the idea of the dam after her first visit in 1967, seeing images of its concrete face and transmission towers, spillways and tailraces through her inner eye in the most unlikely places, and wondering why the place was so affecting. Affecting, beyond the usual emotions that these vast monuments to achievement and lost lives have provoked; that have led to stock phrases (they made the desert bloom) or heroic artworks (bronzes of muscular citizens clutching sheaves of wheat). On the second visit the Reclamation man explains a marble star map, then afterwards, out in the desert towards sunset, Didion begins to understand the cause of her fixation.

I walked across the marble star map that traces a sidereal revolution of the equinox and fixes forever, the Reclamation man told me, for all time and for all people who can read the stars, the date the dam was dedicated. The star map was, he had said, for when we were all gone and the dam was left. I had not thought much of it when he had said it, but I thought of it then, with the wind whining and the sun dropping behind a mesa with the finality of a sunset in space. Of course that was the image I had seen always, seen it without quite realising what I saw, a dynamo finally free of man, splendid at last in its absolute isolation, transmitting power and releasing water to a world where no one is.

It is possible but not always easy to sense this other life of objects; a condition of things that is beyond metaphor and message, and in peculiar moments — perhaps as a type of disengagement with their accretions of meaning — sense them as things at least partly free of human points of reference and symbolism. Can objects be disinterpreted? I think never. Only by the annihilation of the thinkers. The object needs our absence to bring its other life to fullness.

Didion’s massive, roaring dynamo, still transmitting power and releasing water to a world empty of humans is a thought, in its vastness and finality, sublime. In the absence of people this thing will become nameless, unthought of, unthinkable, and finally being (no longer suggesting) nothing beyond itself.

2017

Notes:

Joan Didion *

The White Album

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009

Essay: The Dam, 1970