Uncategorized

Rhythm

If you walk through any Australian pastoral grassland, taking a route that allows your journey to effortlessly follow the shape of the land, you may also be walking along an ancient path used by other people; an artefact of sorts, of the travels and rhythmical movements of earlier lives.

The artefact may be invisible; still there, however, buried in the ground below your feet as you walk along a ridge or through a gap between two hills or beside the remnant shoreline of an old sea. The ancient path still exists, as traces that may only be detectable as a subtle shift in the colour or compaction of the earth, or as charcoal left from a hundred hearths dotting places along the way — or it could be wholly visible, as a present day road that traces the old journeys.

In 1947 the Art Gallery of New South Wales purchased a small painting by Australian artist Lloyd Rees. Painted in Gerringong on the states south coast The Road to Berry has captured a ‘rhythmical movement’ (Rees’s words) in the scene — the curves of the roads and fencelines, the folds of the hills, the placement of houses as two patches of vermilion in an otherwise sombre grassland — an atmospheric landscape, sensory in its effect on people, that appears to have touched many, including myself.

***

Australia, 1940s. A man sits under a tree in Gerringong, southern New South Wales. He looks at a road winding through some grass covered hills; and, allowing that artists are free to invent whatever they ‘see’: he sees clouds (probably), houses (probably), scatterings of trees (most likely). The small canvas board in front of him is still blank but the landscape is loaded.

We can’t know what he is thinking, or if what he is thinking has anything to do with the rhythmical movement he applies to the canvas that he later says, ‘just happened’. We can know however, with only a little magical thinking that the rhythm and movement is already there — under the hills, running through the grassy slopes, inside the houses, floating through the woven air of the sky — ancient pathways, changing seasons, old climate patterns, species evolving and becoming extinct, billions of births and deaths, houses, ruins, shifting shorelines, moving fencelines. The unwritten history of the landscape’s rhythmical movement is inseparable from the moment’s fleeting view.

Something of the landscape got into a person sitting under a tree in Gerringong. We can often sense this, without needing to understand why — that when we enter a landscape the landscape enters us.

*

Lloyd Rees quote from the Art Gallery of New South Wales web archive:

The Road to Berry is a tiny picture I remember painting from under a copse of trees … and I just remember a small canvas and a sort of rhythmical movement that just happened; I was always amazed at the attraction it had … I was never able to repeat that little picture, and that’s a good thing.

artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/7940

Bones

If you walk through any Australian pastoral grassland you will probably come across scatterings of animal bones: the remains of cattle, sheep, horses and native marsupials, particularly kangaroos.

When an animal dies, out in the open landscape, its flesh and bones quickly become flung about over a wide area by feral dogs and cats, foxes, dingoes and crows.

At first glance there is nothing outwardly beautiful about these random scatterings of gnawed bone, cartilage, hide and torn fur, but gradually, if you stand there in the sun and wind and waving grass, thinking about what went before, perhaps imagining the plight or sentience of the animal before it fell, you can have an understanding of the temporal nature of the dance: the animal’s birth and death, the seasons it lived through, the time it lived under the same sun and sky as you, and the time it takes for a creature to return into the earth.

If you are thinking this way about these lives that until this moment had gone unnoticed by you, unwitnessed and unrecorded, you may have reached a point of transition, a point in the dance, at which the shattered scraps around your feet will be seen as beautiful.

The beauty lies not solely in your sharpened sense of empathy, not only in the elemental sadness the scene presents, only partly in the inexplicable power of some broken bones to reshape your awareness of your own presence in the dance — but almost entirely in the silence that surrounds each object: each splintered bone, each scrap of torn fur, every stem of waving grass.

* * *

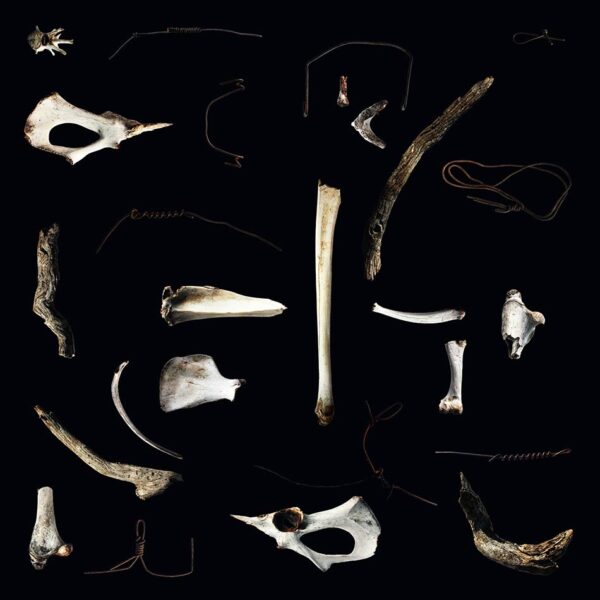

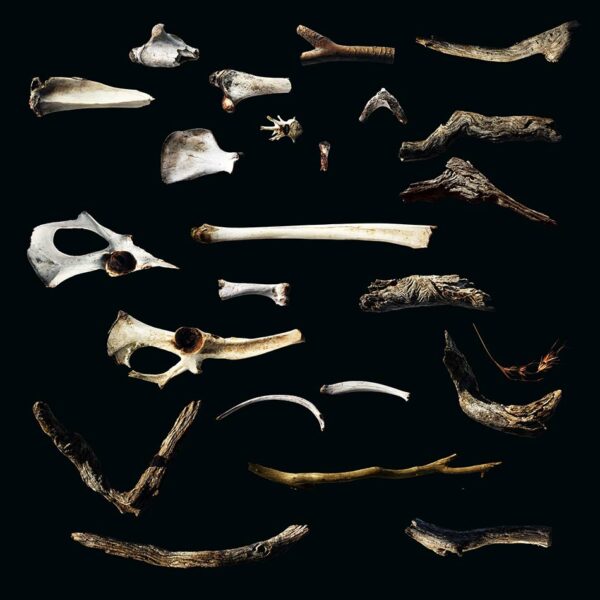

6 scarves on silk crepe de chine:

Bones scarf 1

100 x 100 cm

Bones scarf 2

100 x 100 cm

Bones scarf 3

53 x 53 cm

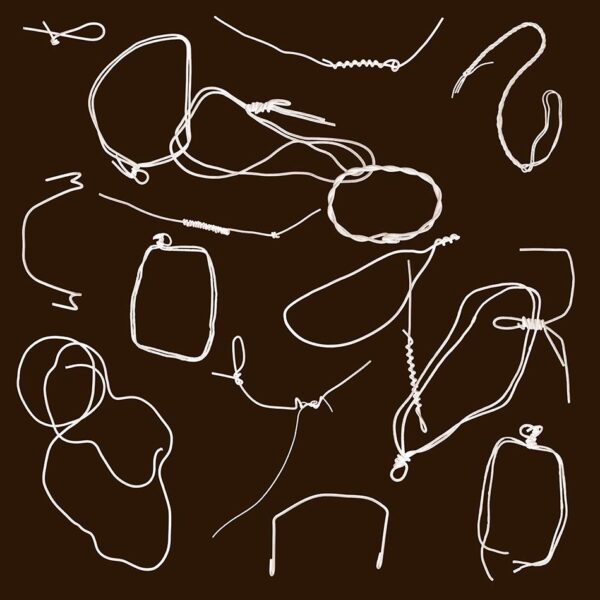

Fence wire scarf brown

100 x 100 cm

Fence wire scarf blue

100 x 100 cm

Tin can scarf

100 x 100 cm

Scarf design GS

Thaw

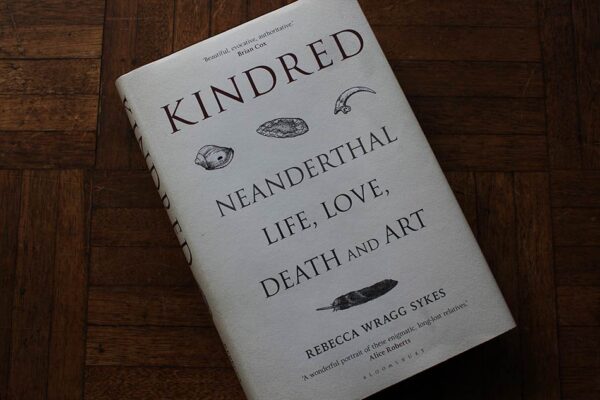

Neanderthals

Sykes invites us to let our guard down, to ‘Push against the impossible, and perform a quantum shift back in time to the Pleistocene. Close your eyes and pick a world: a grassy plain under a cool winter sun; a warm forest track, soft loam underfoot; or a now-sunken rocky coast, gulls’ cries salting the air. Now listen, step forward, she’s here:’

When you’re close enough, press the skin of your palm against hers. Feel her heat. The same blood runs under the surface of your skin. Take a breath for courage, raise your chin, and look into her eyes. Be careful, because your knees will weaken. Tears will come to your eyes and you will be filled with an overwhelming urge to sob. This is because you are human. *

Kindred. Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art

Rebecca Wragg Sykes

Bloomsbury 2020

*

Quote

Prologue, The Last Neanderthal

Claire Cameron

Charcoal, bone, rock

Some things seem to ask for less interpretation than others.

Possibly, because I came from an advertising background, then graphic design, where communicating a reason to buy counts for a lot, moments that don’t overtly contain a message are often more appealing than those that do; moments that feel less contrived; more elemental. Charcoal / Bone / Rock. Mindless, repetitive, somehow comforting and still-making, like an incantation or a recitation.

Of course interpretation is always there. In my current state-of-mind and with these long shadows cast by a low winter sun, this one comes easily.