Pocketbook

The Other Room

The Other Room is taken from Undefinable Places In-between—a series of short essays I have written, and continue to write, under that title.

The Other Room

There are many ways to perceive things that exist — as particles or energy, as being real or imagined, as object or concept, presumed or proven, visible or invisible. Some deep thinkers ask the question, Does existence exist? And some, perhaps more inclined to doublethink, impose perceptions of nonexistence on things that exist by making their nonexistence official.

Countries with oppressive systems of government typically have many places that officially don’t exist. Particularly those rooms, buildings, facilities or precincts that result from perceptions of the lives of certain others being of lower value or a threat to the life and values of the regime.

Before 1989, this room and the prison that surrounded it, did not officially exist. It could not be found on GDR street maps and it could not be located, even internally, by the people held captive within. Prisoners had no idea of where they were geographically or with whom, as inmates, they shared this non-place with.

In the adjoining room out of shot:

there would have once been an identity left threadbare through torture, interrogation and isolation, with a number for a name.

On this side of the wall:

there would have been a gross accumulation of intimate details on the same identity, obsessively compiled through the surveillance mechanism of the State.

Much has been written about the attractions of Berlin to visitors. The current freedoms as well as the old repressions, the over romanticising, the overwhelming history of the place and its dark seduction, and that perennial question: How could all this happen? And the reality is that it still is happening —in many places around the world.

Australia is not an exception.

The new secrecy and ugly nationalism creeping into Australian politics is worrying. The potential slide into oppressive government is beginning to appear to be held less in check than we once thought.

This pattern should sound familiar:

increased official secrecy and a push to control the media and the arts, the singling out of minorities as a threat to public safety, indefinite detention of adults and children, government initiated campaigns of fear, the silencing of critics, the eroding away of fundamental human rights, the prospect of draconian sentences for simply reporting the wrongs, the threat of losing citizenship, escalating surveillance — all of it, always, in the name of national security.

Notes:

Custodial judges’ room in the former prison of the Ministry of State Security, Berlin Hohenschönhausen.

Thanks to Jennifer Kunze, Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen, for explaining the function of the room in my photograph.

Photograph, GS.

No Message

No Message is taken from Undefinable Places In-between—a series of short essays I have written, and continue to write, under that title.

No Message

It has been a struggle to write this. Why this place has affected me in the way it has. It was liberating, but not for any reason I could easily identify at the time. And liberating in what way?

On reflection, one obvious and highly explored line of reasoning has been centred around the idea of the indifference of nature — and the realisation of this actuality, the cold beauty of this thought, can affect you deeply.

I stand in this paddock, in the middle of all this beautiful indifference: the grass growing, the long early morning shadows growing shorter, the sun rising, the breeze starting up, and the whole thing feels so enduring. I stand there with a camera around my neck and a head full of volition, thinking about how to get some decent photos, overlayed with what to have for breakfast, overlayed in there somewhere with a dozen wishlists built around the quest for a better life, most of them connected, directly or indirectly to money… or health, or perseverence or luck. Even with all this volition, at best in this place I am incidental. It can do without me.

Perhaps not being needed, to be inconsequential—and realise it—is a form of liberation.

Another way of thinking about this landscape, akin to indifference, is that this is a place that has no messages.

Although it could be argued that even a landscape devoid of text or any standard communications medium has messages; for instance, a wordless statement about competent land management coming from the way a grove of trees has been planted or the way the grass has been mown, but these are messages that have been consciously or unconsciously overlaid. Or it may be argued that a pristine piece of forest has many messages for us —about beauty, about systems working in harmony, about being a natural reservoir of pharmaceutical knowledge, whatever… but these messages are interpretations — imaginings in the minds of humans. The natural world isn’t trying to tell us anything. Trees have no agenda and grass is not out to shift opinions. All of this nature is utterly, unspeakably, beautifully mute.

We need these unspeaking places. Now, more than ever, because of predatory marketing, political spin and outright political lies, the injustices behind relentless corporate lobbying, the pap and crap of Linkedin must-read emails, most motivational speakers, public hospital wings named after supermarket chains…

As necessary as the better end of messaging may be, the noise that overlays the natural world is constantly saying, You should be doing this; you need to be like this; you should be thinking this…

This is the other form of liberation (I think) I have identified: the freedom to feel, be subsumed or taken over, affected, purely by the way things are. The freedom to ‘get it’, to have some understanding of the way it is, using your own senses, intelligence and intuition, rather than submitting to the opinions or agendas of others. This is a ‘gift’ of the natural world that I am cautiously calling truth. Cautiously, because the term has been hijacked (no great secret here) by some of the world’s most skilful and mendacious message-makers.

Here is a heartening thought, however. No matter how much messaging overlays the natural world — even in the most message-overlaid places: the Shibuya crossing in Tokyo, the aisles of a large suburban supermarket, the front benches at Parliament House Canberra, the laptop holding the junk mail in your email inbox—the nature quietly remains. It may have been battered and bruised, reconfigured, covered over and forgotten, but it will not go away, and although it will never have anything to say, it will always have a measureless capacity to inform every cell in your body.

Notes:

Maffra is a small rural district along the banks of the Snowy River in Southern New South Wales, Australia; not far from the towns of Dalgety, Jindabyne and Berridale. Summers are hot. Winters are cold. I’m told the wind blows most of the year and it doesn’t rain much. It’s dry and grassy. It’s in the rainshadow of the mountains nearby.

Photograph, GS.

Subterranean Garden

Subterranean Garden is taken from Undefinable Places In-between—a series of short essays I have written, and continue to write, under that title.

Subterranean Garden

Under a hill in Mittagong, New South Wales, there is this dark, subterranean garden. The hill is a piece of the rim of an ancient volcano, and the garden—laid down in an old single-line railway tunnel—is over half a kilometre long and sealed at either end with high security steel doors.

Inside, exotic mushrooms are grown from cylinders of compressed eucalyptus sawdust. The eucalyptus ‘logs’ are evenly spaced on steel grids that line either side of the tunnel. The concrete floor appears to be a continuous, door-to-door slab.

These concealed places are deeply attractive; although the word ‘attractive’ by itself hardly covers the uncanny feeling that something magical could also be present, as well as something slightly menacing.

‘Enchantment’, in this instance, is probably not too fanciful a word to cover a range of feelings or atmospheres that these hidden places evoke.

Secret gardens, grottoes, wells, the Underworld of the ancient Greeks, ‘bottomless’ lakes, limestone country sinkholes, the earthy home of Mole in Wind in the Willows, the lairs of oracles and hermits, burial chambers, crypts, deep caves holding yet-to-be-discovered prehistoric paintings, the imaginary underground dwellings of all manner of ‘little folk’, and hollows under hills that in European mythology were usually occupied by strange otherworldly beings — are all places of enchantment.

Notes:

Li Sun Exotic Mushrooms is a mushroom farm between the Southern Highlands towns of Mittagong and Bowral in New South Wales, Australia.

Mittagong is said to be the local Aboriginal word for Little Mountain*. It refers to the hill through which the railway tunnel is cut. On maps its name is Mount Gibralter.

I regret not also being able to tackle this writing from the point of view of pre-European history and mythology. This region must have been rich in flora and fauna and would have supported many people in those thousands of years before colonisation — and it would have had a rich history and mythology to go with it.

Like most places in Australia, particularly those farmable areas occupied early by Europeans, much of the Indigenous history has been lost along with the languages. The Eurocentricity of the last paragraph in my garden story is evidence of this lost knowledge.

*

Mr K R Cramp, Secretary

Royal Historical Society of New South Wales

Sydney Morning Herald

21 October 1924

Photograph, GS.

Disappearing

Disappearing is taken from Undefinable Places In-between—a series of short essays I have written, and continue to write, under that title.

Disappearing

Things disappear in different ways. A thing can be physically extracted from the landscape, like a suitcase stolen from the pavement while you pay the airport taxi. Or it can go of its own volition: a straying cat.

Things often leave the realm of our senses through our own intent. Choosing not to see, touch, hear or think about something is essentially the same as making it absent. Everything disappears from our field of vision as we walk from one room to another, down a familiar street, past unfamiliar faces in a crowd in a foreign city, and even if we, again, view the object or the face at another time, on another day, the exact appearance will never be the same as the one that went before.

In this way, disappearances are common, thousands of them happening to everyone everyday, but even when the transformation—the going from a state of ‘there’ to ‘not there’ happens as the most commonplace event, the gap between those two conditions can be beautiful, unforgettable, astonishing and pivotal.

In the Russian film, Mirror, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, a boy, Ignat, is asked to read aloud from a notebook by a woman sipping tea at a polished table in an apartment. The boy reads to her for several minutes until the door bell rings. She asks Ignat to go and answer it. When he returns, alone, both woman and teacup have disappeared, and the only evidence of their having been real is the fast-evaporating circle of moisture left by a hot teacup on a varnished table.

What follows is an intense and transfixing moment. As the evaporating patch, in close-up, becomes smaller—accompanied by a spare choral arrangement with voices rising in pitch as the exact moment of disappearance is approached—I find myself at each viewing, completely taken up by this little sequence of film and sound; being hurtled towards the same point of nothingness, an exquisite, elusively precise point; one point between many others, the distance between them immeasureably reducing to a tiny spot that was reached on a varnished tabletop, on a film set, in front of a camera, in the USSR, in 1974.

Notes:

Film, The Mirror,

Andrei Tarkovsky, 1975

‘the life force of music is materialised on the brink of its own total disappearance.’

Andrei Tarkovsky,

Sculpting in Time.

‘Because the faculty of sight is continuous, because visual categories (red, yellow, dark, thick, thin) remain constant, and because so many things appear to remain in place, one tends to forget that the visual is also the result of an unrepeatable, momentary encounter. Appearances, at any given moment, are a construction emerging from the debris of everything which has previously appeared.’

John Berger

Berlin

Berlin is taken from Undefinable Places In-between—a series of short essays I have written, and continue to write, under that title.

Berlin

How can a place have—in the same moment—something and nothing in-between the things that define its edges? Be loaded and empty at the same time?

In a city, a volume of air can be enclosed by walls, or a fence, a gate, a painted line, or a neatly ordered adjacent patch that provides delineating contrast to the rubble and weeds next door—essentially appearing to be a patch of nothing—and still, it feels infused with something powerful, unfathomable.

It’s even harder to define exactly what it is that resides within a psychological space; Berlin seems full of them: the liminal places, unspeaking places, and those in-between places and charged zones of emptiness; gaps between ‘there’ and ‘not there’.

It’s hard to define what it is, but I would like to know, because then I would better understand Berlin, and probably learn something about all cities.

Notes:

Mauer Park, Berlin.

Photograph, GS.

Pecha Kucha Night at UNSW Art & Design

Above: Vanessa Low

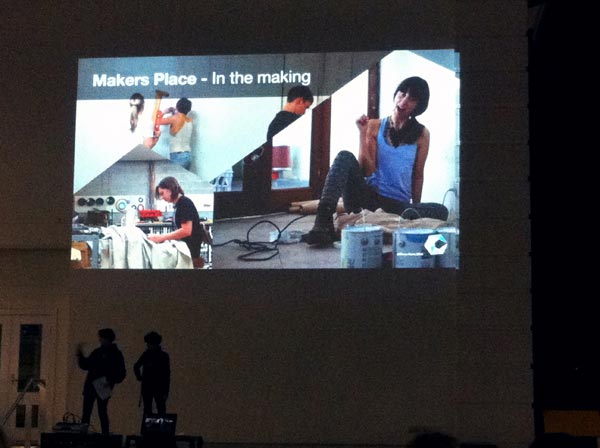

My two friends and work buddies, Heidi Dokulil and Beatrice Chew, are the producers for Pecha Kucha Night in Sydney. Pecha Kucha is the 20 seconds-per-image talk series that was born in Tokyo at SuperDeluxe—the Roppongi bar and venue that is ‘open most nights for thinking and drinking’.

The wall at one end of UNSW’s courtyard was a particularly good surface for the pictures. The theme for Pecha Kucha Night 25 was Collecting.

Only some of the speakers are represented here in images; next time I will take a decent camera!

Above: Vanessa Low

Above: Vanessa Low

Above: Grace Turtle & Melissa Fuller, Three Farm

Above: Nick Rudenno & Miguel Sicari, Nowhere Famous

Above: Clinton Bradley

Speakers

Grace Turtle & Melissa Fuller, Three Farm

Describing herself as a Social Design Strategist, Grace believes that the role of designer has shifted to facilitator, therefore to be an effective designer you need to teach and provide the community with tools to learn. Grace is a graduate of COFA and the co-founder of Three Farm, a social design enterprise specialising in new manufacturing technology and processes that enhance social learning, design and sustainable practice. Melissa describes herself as the “maker of makers” and is a passionate advocate of social equality.

Nick Rudenno & Miguel Sicari, Nowhere Famous

Nowhere Famous tells stories through design, art direction, typography, illustration,vcreative direction & web with collective collaboration at the core of everything they do.

Vanessa Low

Vanessa Low is a UNSW Art & Design alumna, having finished her bachelor of Art Theory here last year. She is now a freelance arts writer, photographer and blogger who has contributed to Elle, Popsugar and Art & Australia. Her penchant for collecting is derived from her fear of forgetting and love of asking questions, documented on her blog The Monday Issue over the past 6 years.

Sacha Pantschenko

Sacha Pantschenko is a product designer living in Sydney. Working across many disciplines in the industry over the last 10 years, he is always looking to new and engaging ways to innovate and rethink how things work. Sacha has recently headed up one of the largest product design crowdfunding campaigns in Australia. He is easily distracted good burgers and craft beers.

Judith Torzillo and Victoria Cleland, Young Collectors

The Young Collectors are Judith Torzillo and Victoria Cleland. Emerging contemporary jewellers and collectors, Judith’s jewellery is focused on viewer engagement and exploring the physicalities of wearing and seeing. Victoria’s jewellery practice investigates notions of value, image and wealth. Together they host events that connect artists and collectors.

Clinton Bradley

Clinton Bradley likes art and dumplings. He collects art by a small group of artists that often feature animals [often in the most opaque of ways] and eats dumplings wherever he can find them. Clinton has collected from as far back as he can remember and counts house plants, crystals, Japanese scrubbing brushes, finger-nail clippings and taxidermy among the many things that have caught his attention over the years.

Text on speakers by Heidi Dokulil, Good Habitat

The wall.

Subterranean garden

Under a hill in Mittagong (the rim of an ancient volcano) there is a 600 metre long mushroom farm; a dark, subterranean garden in an old, single line railway tunnel, full of strange shapes and beautiful textures. It reminded me of Susan Sontag’s brilliant essay on grottoes: A Place for Fantasy.

Li Sun Exotic Mushrooms, Mittagong, New South Wales, Australia.

Susan Sontag, A Place for Fantasy; Where the Stress Falls, 2001.

Stairs

Gehry in Sydney is the title of a book I have been working on with Managing Editor and writer, Liisa Naar, at the University of Technology, Sydney. The Gehry Partners designed Dr Chau Chak Wing Building (UTS Business School) in Ultimo, Sydney, has this beautiful staircase that is worth seeing when the building opens soon. Unfortunately my point-and-click level of photography is not up to capturing this. The professional photography in the new book will be.

Gehry in Sydney

The Dr Chau Chak Wing Building, UTS

Edited by Liisa Naar and Stewart Clegg

Maffra, New South Wales, 6:30am

Maffra, New South Wales, 6:30am