Pocketbook

Rhythm

If you walk through any Australian pastoral grassland, taking a route that allows your journey to effortlessly follow the shape of the land, you may also be walking along an ancient path used by other people; an artefact of sorts, of the travels and rhythmical movements of earlier lives.

The artefact may be invisible; still there, however, buried in the ground below your feet as you walk along a ridge or through a gap between two hills or beside the remnant shoreline of an old sea. The ancient path still exists, as traces that may only be detectable as a subtle shift in the colour or compaction of the earth, or as charcoal left from a hundred hearths dotting places along the way — or it could be wholly visible, as a present day road that traces the old journeys.

In 1947 the Art Gallery of New South Wales purchased a small painting by Australian artist Lloyd Rees. Painted in Gerringong on the states south coast The Road to Berry has captured a ‘rhythmical movement’ (Rees’s words) in the scene — the curves of the roads and fencelines, the folds of the hills, the placement of houses as two patches of vermilion in an otherwise sombre grassland — an atmospheric landscape, sensory in its effect on people, that appears to have touched many, including myself.

***

Australia, 1940s. A man sits under a tree in Gerringong, southern New South Wales. He looks at a road winding through some grass covered hills; and, allowing that artists are free to invent whatever they ‘see’: he sees clouds (probably), houses (probably), scatterings of trees (most likely). The small canvas board in front of him is still blank but the landscape is loaded.

We can’t know what he is thinking, or if what he is thinking has anything to do with the rhythmical movement he applies to the canvas that he later says, ‘just happened’. We can know however, with only a little magical thinking that the rhythm and movement is already there — under the hills, running through the grassy slopes, inside the houses, floating through the woven air of the sky — ancient pathways, changing seasons, old climate patterns, species evolving and becoming extinct, billions of births and deaths, houses, ruins, shifting shorelines, moving fencelines. The unwritten history of the landscape’s rhythmical movement is inseparable from the moment’s fleeting view.

Something of the landscape got into a person sitting under a tree in Gerringong. We can often sense this, without needing to understand why — that when we enter a landscape the landscape enters us.

*

Lloyd Rees quote from the Art Gallery of New South Wales web archive:

The Road to Berry is a tiny picture I remember painting from under a copse of trees … and I just remember a small canvas and a sort of rhythmical movement that just happened; I was always amazed at the attraction it had … I was never able to repeat that little picture, and that’s a good thing.

artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/7940

Bones

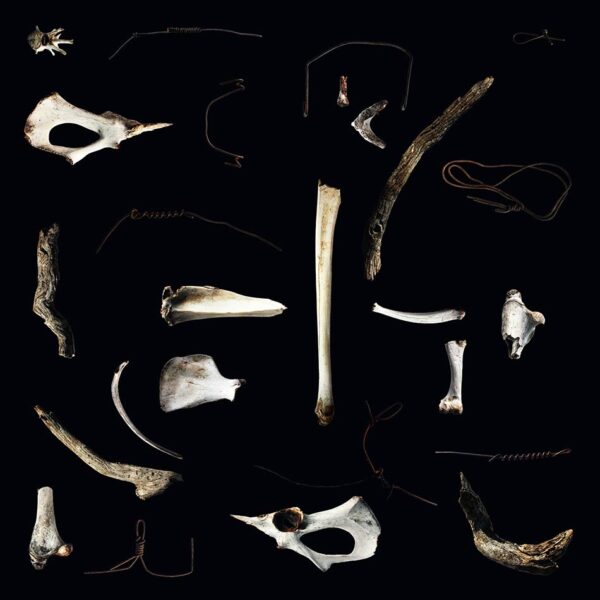

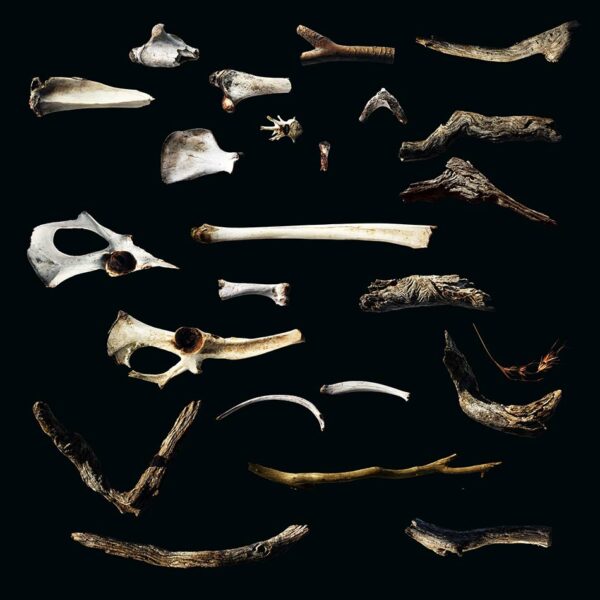

If you walk through any Australian pastoral grassland you will probably come across scatterings of animal bones: the remains of cattle, sheep, horses and native marsupials, particularly kangaroos.

When an animal dies, out in the open landscape, its flesh and bones quickly become flung about over a wide area by feral dogs and cats, foxes, dingoes and crows.

At first glance there is nothing outwardly beautiful about these random scatterings of gnawed bone, cartilage, hide and torn fur, but gradually, if you stand there in the sun and wind and waving grass, thinking about what went before, perhaps imagining the plight or sentience of the animal before it fell, you can have an understanding of the temporal nature of the dance: the animal’s birth and death, the seasons it lived through, the time it lived under the same sun and sky as you, and the time it takes for a creature to return into the earth.

If you are thinking this way about these lives that until this moment had gone unnoticed by you, unwitnessed and unrecorded, you may have reached a point of transition, a point in the dance, at which the shattered scraps around your feet will be seen as beautiful.

The beauty lies not solely in your sharpened sense of empathy, not only in the elemental sadness the scene presents, only partly in the inexplicable power of some broken bones to reshape your awareness of your own presence in the dance — but almost entirely in the silence that surrounds each object: each splintered bone, each scrap of torn fur, every stem of waving grass.

* * *

6 scarves on silk crepe de chine:

Bones scarf 1

100 x 100 cm

Bones scarf 2

100 x 100 cm

Bones scarf 3

53 x 53 cm

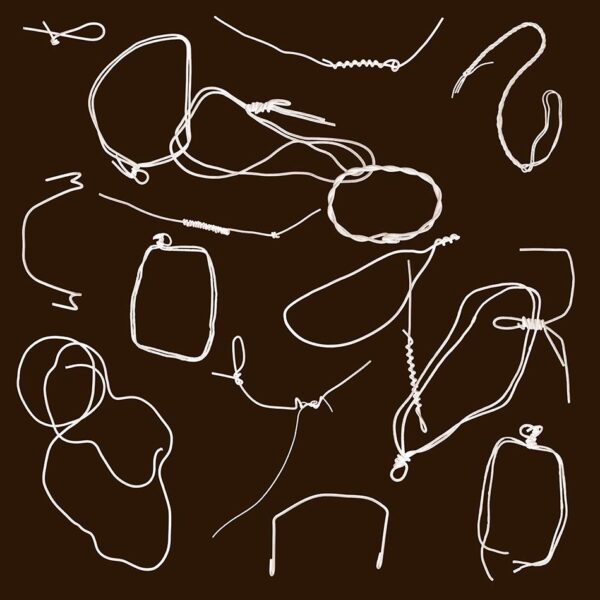

Fence wire scarf brown

100 x 100 cm

Fence wire scarf blue

100 x 100 cm

Tin can scarf

100 x 100 cm

Scarf design GS

Thaw

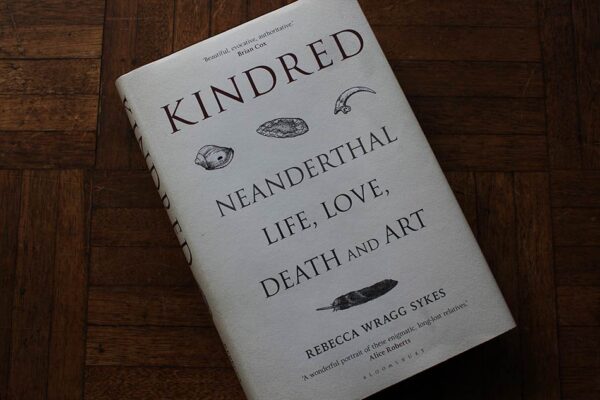

Neanderthals

Sykes invites us to let our guard down, to ‘Push against the impossible, and perform a quantum shift back in time to the Pleistocene. Close your eyes and pick a world: a grassy plain under a cool winter sun; a warm forest track, soft loam underfoot; or a now-sunken rocky coast, gulls’ cries salting the air. Now listen, step forward, she’s here:’

When you’re close enough, press the skin of your palm against hers. Feel her heat. The same blood runs under the surface of your skin. Take a breath for courage, raise your chin, and look into her eyes. Be careful, because your knees will weaken. Tears will come to your eyes and you will be filled with an overwhelming urge to sob. This is because you are human. *

Kindred. Neanderthal Life, Love, Death and Art

Rebecca Wragg Sykes

Bloomsbury 2020

*

Quote

Prologue, The Last Neanderthal

Claire Cameron

Things on a blackboard

Grass.

Kangaroo grass is an ornamental looking native species that covered more ground in Australia in 1788 than it does in 2021. A neighbour said that when his settler forebears rode their horses through the summer grasslands the high, sun-ripened heads clicked on their stirrups for kilometres at a time. This remark, or something close to it, was poetic I thought, and in that, unexpected.

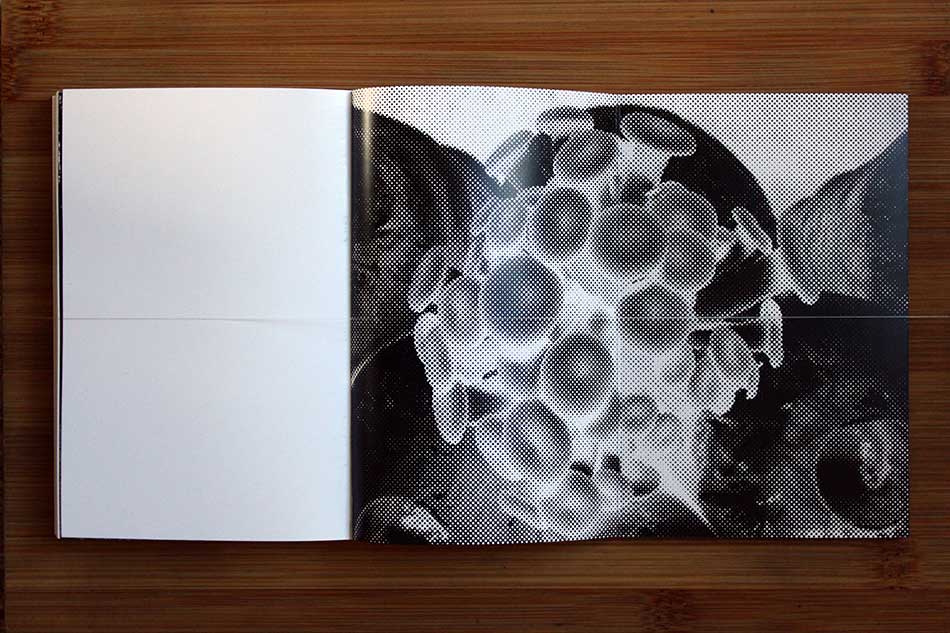

Bone.

The ground in many places in rural Australia is covered, no longer in kangaroo grass, but the bones of animals: cattle and sheep, horses, other introduced species like rabbits — and native marsupials, particularly kangaroos. When an animal dies its bones quickly become flung about over an area much wider than its body-space, by feral dogs and cats, foxes, dingoes and crows.

When I look at these bones, their shapes made more lucid than they were in the paddock by the blackboard’s flat monochrome, I can imagine them inspiring ideas for architectural forms. The Sydney Opera House roof shapes allude to the sails of yachts on the harbour. The designer, Utzon, came from a sailing family. One of these bones could be an aerial view of a house or a waterborne concert hall skimming or hovering over a dark sea. Beyond this they are beautiful for precisely what they are and were and will be.

Charcoal.

One of the satisfying things about a charcoal stick is that it lets the body think less strategically than the head. There seems to be less intent, definitely less control, in a swinging, arcing arm holding a piece of brittle burnt tree and putting a mark on an A0 sheet of paper than there is in making a 0.3pt line on an InDesign page with an index finger on a trackpad the size of a beer coaster. It creates the unexpected; it feels something like receiving a gift from out of the blue, when it shatters and snaps, and covers the paper in unplanned scratches and hand smudges.

Pomegranate.

A fruit loaded with meaning along with its jewel-like seeds. European myths. Persephone. Orpheus and Eurydice. The underworld. The writings of Virgil and Ovid. Operas by Stravinsky and Gluck. Death and regeneration.

Charcoal, bone, rock

Some things seem to ask for less interpretation than others.

Possibly, because I came from an advertising background, then graphic design, where communicating a reason to buy counts for a lot, moments that don’t overtly contain a message are often more appealing than those that do; moments that feel less contrived; more elemental. Charcoal / Bone / Rock. Mindless, repetitive, somehow comforting and still-making, like an incantation or a recitation.

Of course interpretation is always there. In my current state-of-mind and with these long shadows cast by a low winter sun, this one comes easily.

How to wear a tree

Most textile dyeing happens, along with the weaving and cutting and sewing, in factories, mills and industrial workrooms in places unnamed and far away from Australia. Outside their own living environments the people who do the work are unthought of and undervalued. They are usually underpaid.

We are surrounded, almost non-stop, by textiles. They envelop our bodies and protect us, keep us warm, adorn our homes, make statements that are highly personal, help redirect anxieties and yearnings, allow us to conform or not conform, stand out or become invisible, and they saturate our visual and haptic and subliminal worlds.

Yet within these worlds of intimate connectedness to fabrics we are almost always profoundly disconnected from their beginnings.

+++

Samorn Sanixay is a Canberra-based textile designer who uses natural dyes for the fabrics she either weaves herself or has made by the weavers in their co-operatively owned studio in Vientiane, Laos. For her locally (Australian) dyed pieces the colouring materials are found during short but frequent foraging expeditions around the streets, parks, domestic gardens and industrial zones of Sydney, Canberra and regional New South Wales.

Some of these colour sources are materials one would expect: flowers, plants, seed pods — things purely botanical. Other sources are less expected: riverine mud, leftover fruit and vegetable scraps from the evening meal, rusted machine parts, the decaying leaves and dark, gritty sludge you clean from roof gutters in the southern Australian autumn.

About a year ago Samorn gave me a pink silk scarf. I like it for several reasons. I like the texture of the openly woven silk and its deliberately frayed edges. The way the pink, with just a hint of Prussian blue (the colour, not the chemical) sings against my current, unadventurous, econo-wardrobe of mostly dark navy. And I like where the pink comes from: the plump berries of a lilly-pilly in the front yard of Samorn’s house.

This is a type of attachment to place you could never have, say, through a scarf bought from an international clothing retailer, or even, regardless of the beauty of their immaculately screen printed silks, Hermes. I think this is not too much of an overplay; the thought that the scarf directly connects me to a tree. I’m wearing some of a tree. I can visit it. It has a street address.

In late April 2019 I went for a walk with Samorn and Heidi Dokulil through Botany, a suburb of inner Sydney with a colonial history that some Australians have conflicting feelings about. This is partly because Botany is the site of Cook’s landing and first encounter with the Aboriginal owners, and as a result, the site of some of the first incidents of ill-treatment of the country’s original inhabitants by the British. The other reason is that some Sydneysiders think of Botany as, to use a classic Australian colloquialism,… daggy.

When Cook visited in 1770, Botany Bay was a rich source of food: fish and oysters, birds, goannas, possums, wallabies and edible plants for the Kameygal (spear clan) people on the bay’s north shore. Now the freshwater creeks are covered-over drains and the bushland has been cleared for airport runways and a vast shipping container terminal.

In Sydney’s housing market, Botany is not a longed-for residential address, although its nearness to the central business district and the restlessness of the ever renovating, cashed-up ‘haves’ may soon change this.

Botany has its own charm, however. There are modest houses and cottages in its residential streets with their discreet garden patches interwoven with small factories and trade workshops. The Port Authority has been replanting native species along the shoreline and building paths for walking and cycling that partly run alongside a 4 lane expressway full of semi trailers and tailgating delivery vans. The contrast is striking, and in its own Botany way, beautiful: massive red and yellow cranes hovering over stacks of multi-coloured shipping containers, the growl of gear changing semis against the almost silent (in the far distance) international passenger jets taking off and landing on a seemingly endless, perfectly flat landscape of tarmacs — all of this framed by banksias, coastal she-oaks and tea-trees.

A walk through the reclaimed bushland and residential streets allows a way of seeing Botany that one could not see so fully, through say, a council website, or even a site exclusively dedicated to its history or flora. In the real and many-dimensional world — the one not made of pixels or ink — the place is full of the fragrance of eucalypts and diesel, the sounds of birds and people making stuff with pneumatic hammers and angle grinders, and specifically, for this account, it is a place full of materials for both textile dyes and small unexpected patches of things to eat: plant species, native or introduced; guavas springing up out of roadside verges because someone discarded the remains of their lunch there; tiny private herb gardens hijacking public footpaths between the long-established paperbarks; a big carefully tended bunch of bananas suspended precariously over a tradie’s parked Hilux ute, red dahlias, wild geranium, salvia, pink azalea, bougainvillea, pigface, spiderwort, frangipani, and many invasive species brought in after Cook’s landing.

+++

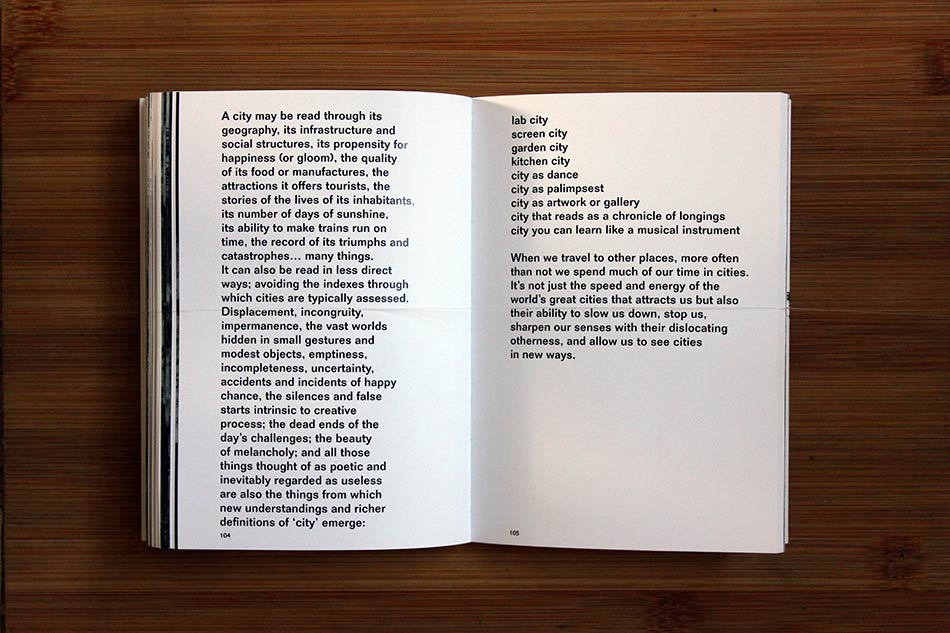

When a person enters a city

There are many criteria from which cities can be measured, and as a result, rated; typically (in urban lifestyle media) for liveability.

For these assessments, presumably questions are put forward. Something like the following.

How efficient is its transport system?

Is it a place with clean air? Clean water?

Does it have quality housing at an affordable price?

Enough jobs? The right institutions? Community services?

A vibrant arts industry? Journalistic freedoms?

Parks and recreational facilities?

Social supports?

Does it create happy tourists?

All of the above being derived from a long list of things we would want to see in a liveable city.

Within that same city of measured train frequencies, housing quality appraisals and stats on career openings, a space also exists for a slower, less indexed, more imaginative type of reflection; with a different set of questions, still connected to liveability and well-being but decoupled from the idea that an inhabitant is somehow always in this state of passive receptivity that the measured city, the city where every desirable attribute has a price, seems to constantly place us.

The city is a collection of first-hand exchanges between a person and a place. When a person enters a city, the city enters that person. How could it not? If you have been touched in the slightest way by a walk down a narrow back lane jammed with flowering frangipani in Sydney’s Darlinghurst, or exhilarated by a chaotic, late night scramble across Tokyo’s Shibuya Crossing, or spent a half day in a shiny shopping precinct fantasising about how the new look could change your life for the better forever, or felt a pang of sadness when passing one more beautiful city building about to be gutted for multi-million dollar apartments — a transference has happened, and some of the city now lives inside you.

Who knows how any of this — a walk through Darlinghurst / empathy for a piece of architecture — can be quantified, but regardless, we know that our senses and imaginations were activated and in effect we have had a conversation with a city that provides more than efficiencies and material guarantees for well-being.

The city of transferences evokes other questions.

What is this place we find ourselves in?

Where are we going?

How can we learn from other cultures?

How can we make this place more fair?

What do we really lose of ourselves when we lose a remarkable building, a language, an historical truth about our colonial past, a 4 million year old marsupial, a 300 year old tree?

We won’t hear these questions being asked in the travel section of a weekend newspaper, or the website of a city’s chamber of commerce, or in a tips list on how to fix Helsinki in an urban lifestyle magazine, or in the glib speech of a right wing politician spruiking the virtues of coal and the urgent need to ramp up national security surveillance. However, within a more poetic framework with which to see cities we can begin to give fragmentary answers at least, to some of the questions in the last paragraph.

What is this place we find ourselves in?

The city is an endless collection of first-hand attachments between a person and a place.

The city is a chronicle of its history that can be read through things lost (species, languages, cultures) and things found (colours, convergences, architectures).

The city is a poetic transmitter; an atmospheric reservoir; a book; a palimpsest; a dance.

The city is a site for the intense convergences of ideas.

+++

Notes:

Samorn Sanixay, Eastern Weft, Australia/Laos

easternweft.com

Graeme Smith, Heidi Dokulil, Good Habitat, Sydney, Australia

goodhabitat.com.au

I like the following set of questions from the Welsh designer/author, John Chris Jones, in his public writing site. From memory, I think he had just read a newly published book on craft in India. (His web archive is so vast I have been unable to relocate the page but this is the text I copied at the time of viewing.)

1

what do we mean by civilisation?

2

what kind of world are we trying to construct (with new media particularly)?

3

how can we improve our perception of ancient cultures… how can we learn from them and achieve a modern way of living to be proud of?

4

is there any way in which the quality of these ancient things and ways of life can be resurrected and shared with everyone?

5

so when is this collective wisdom (from the world of arts and crafts) going to be taken more seriously than banking and profit and the so-called bottom line?…

John Chris Jones

publicwriting.net

Lilly-pilly, Acmena smithii

Australian native, dark-green tree, 8-30 m.

Photography

Botany Bay April 2019

GS

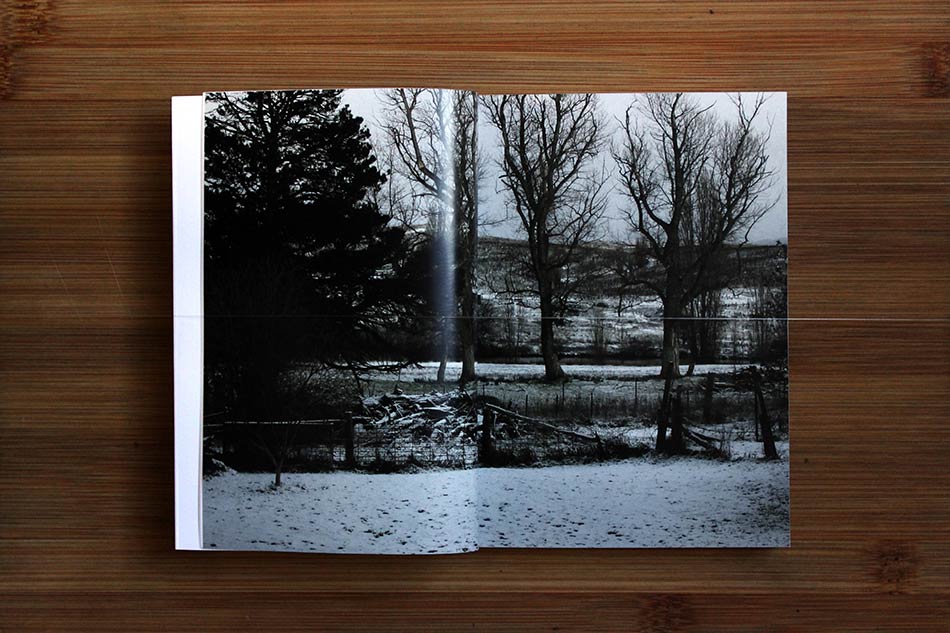

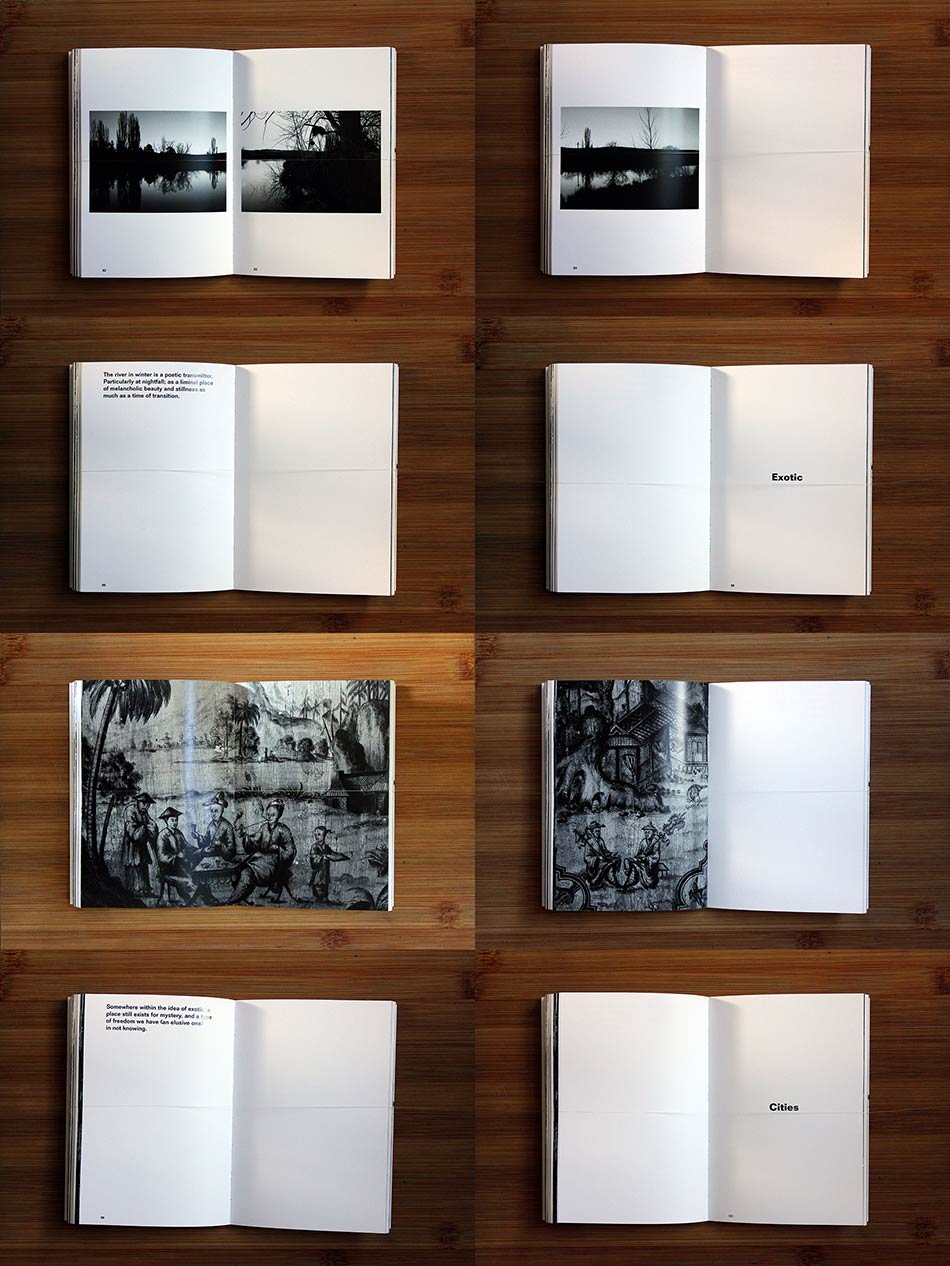

The river in winter

This book began as a larger collection of essays called Undefinable Places In-between. The word ‘essay’ here, has been used with some licence. Two of them are only one sentence long. The river referred to is the Snowy, in southern New South Wales, Australia.

Notes:

The line on page 105, ‘city you can learn like a musical instrument,’ refers to the text in an installation by Robert Montgomery:

<THIS IS WHAT YOU CAN DO / WITH CITIES WHEN YOU LEARN THEM LIKE / MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS>

The River in Winter

Author, photographer, GS, 2019

12 essays, 150 x 105 mm, 160 pages

Exhibition:

Echoes of Voices in the High Towers, Robert Montgomery at the former Tempelhof Airport, Stattbad, Wedding and 20 billboards across Berlin, July-October 2012, presented by Neue Berliner Räume.

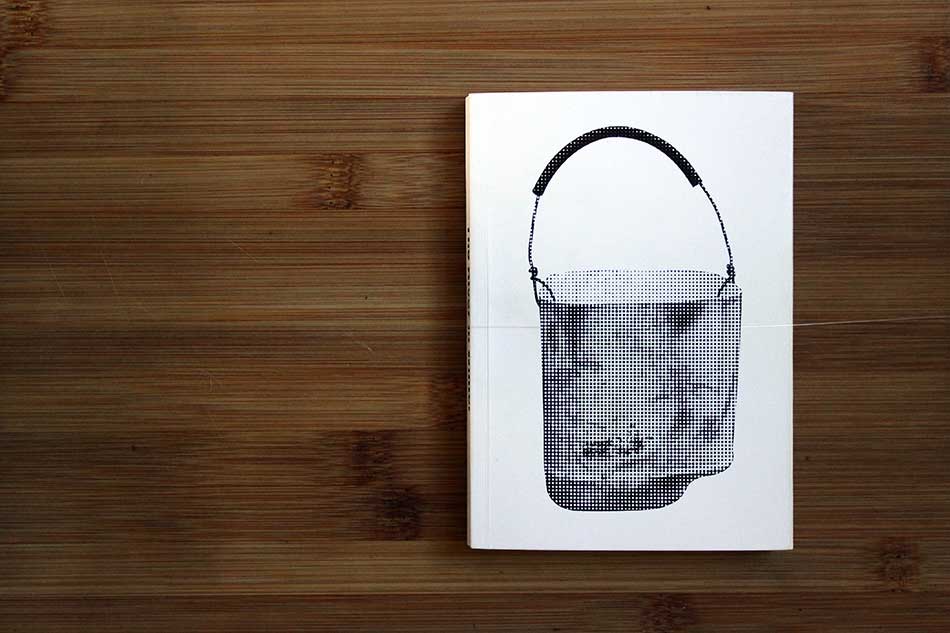

Bucket

A bucket made from an agricultural chemicals container. You could lug house bricks in it and the wire handle would stay fixed through the holes in the heavy duty plastic. The tube around the wire makes it comfortable to hold and more swingable as you walk. I love the look of it — and the idea of it. It would be understandable to think that at least some of the original container, the bit that was cut off, went to landfill. No. It’s a dogs’ bowl.

I never saw a tree

‘I never saw a tree’, says Annie Dillard in Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, ‘that was no tree in particular’. On a tree scale of particularity, eucalypts, in the way they visually chronicle the hard knocks of living in a harsh landscape — all gnarled trunks, shredded bark and broken branches — must be somewhere near the top of that list.

What appeared on screen, however, were not the intended tree photos but pictures of landscape as texture: a less compositional view of landscape, and for someone who thinks about the visual arrangement of objects often, a fresh view with somehow fewer encumbrances.

Suddenly it becomes a place (tree included) of infinite forms and presences and particularities, and it reads as a woven thing, or to skip anything that sounds like creationism, a thing as if woven.

Notes:

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Annie Dillard’s 1974 Pulitzer Prize winning narrative

about living alongside a creek in Virginia, USA

Harper Collins

x

x