Reading cities

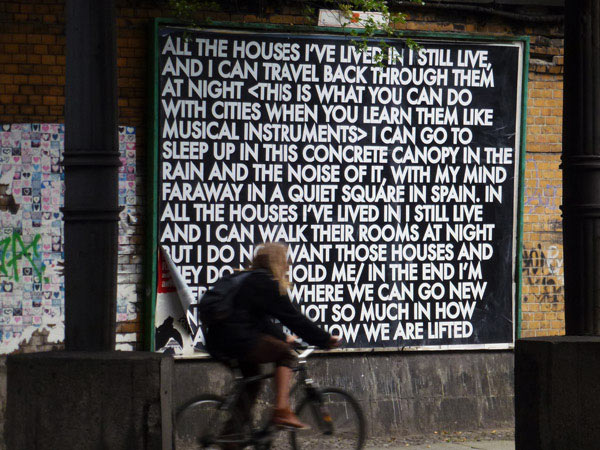

Echoes of Voices in the High Towers, Robert Montgomery at the former Tempelhof Airport, Stattbad Wedding and 20 billboards across Berlin. July–October 2012. Presented by Neue Berliner Räume.

Reading Cities

A city may be read through its geography, its infrastructure and social structures, its propensity for happiness (or gloom), the quality of its food or manufactures, the attractions it offers tourists, the stories of the lives of its inhabitants, its number of days of sunshine, its ability to make trains run on time, the record of its triumphs and catastrophes… many things.

It can also be read in less direct ways; avoiding the indexes through which cities are typically assessed.

Displacement, incongruity, impermanence, the vast worlds hidden in small gestures and modest objects, emptiness, incompleteness, uncertainty, accidents and incidents of happy chance, the silences and false starts intrinsic to creative process; the dead ends of the day’s challenges; the beauty of melancholy; and all those things thought of as poetic and inevitably regarded as useless are also the things from which new understandings and richer definitions of ‘city’ emerge:

lab city;

screen city;

garden city;

kitchen city;

city as dance;

city as palimpsest;

city as artwork or gallery;

city that reads as a chronicle of longings;

city you can learn like a musical instrument.

When we travel to other places, more often than not we spend much of our time in cities. It’s not only the speed and energy of the world’s great cities that attracts us but also their ability to slow us down, to intensify perception, and allow us to have a sense of the gift of things we may otherwise overlook or undervalue.

x

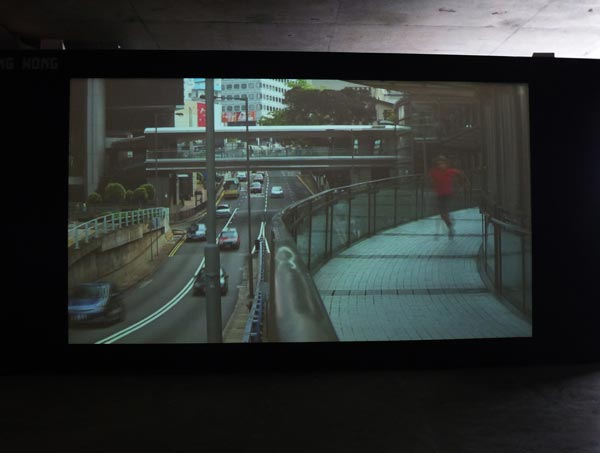

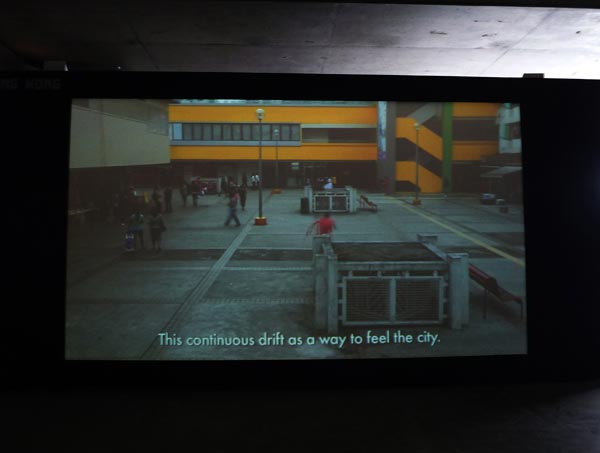

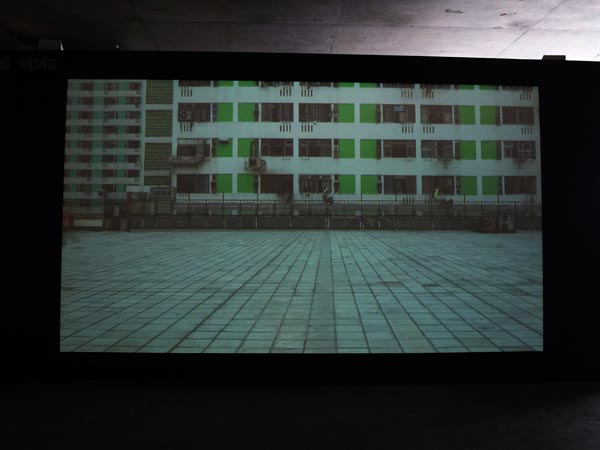

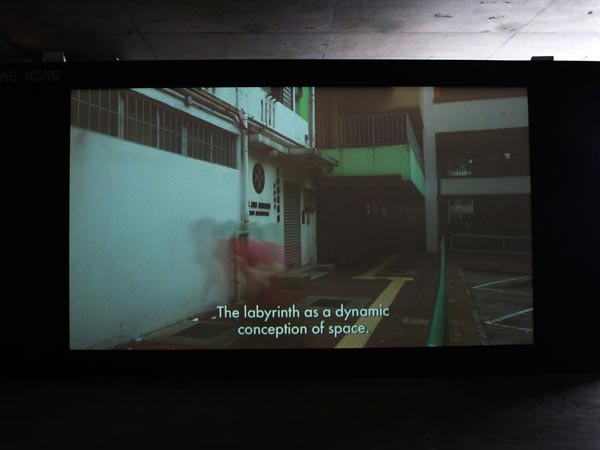

Running the City

‘the city is like a pinball table’; ‘a giant assemblage of prefabricated obstacles’; ‘social space’; ‘to loot space and time’; ‘to be suspicious’; ‘ non linear fragments used for the construction of memory’; newscape’; ‘porous city’; ‘to become invisible for just a few minutes’.

Runscape (Hong Kong), 2010

Single channel HD video, 24:18 mins

Laurent Gutierrez, Valerie Portfaix

x

The Patch, The Shack, The Newsroom

The Newsroom is a workshop for kids between the ages of 8 and 12 from the City of Randwick. The idea is to develop their skills in storytelling and photography while getting a first hand look at how newspapers are made.

Created and developed by The Patch, the good habitat firm of Heidi Dokulil, Beatrice Chew and myself.

Held in partnership with The Shack, a not-for-profit community organisation.

Sponsored by the City of Randwick.

B

A new project by our other good habitat firm: The Patch. The Patch = Heidi Dokulil, Beatrice Chew and myself. Details later.

Visit The Patch

x

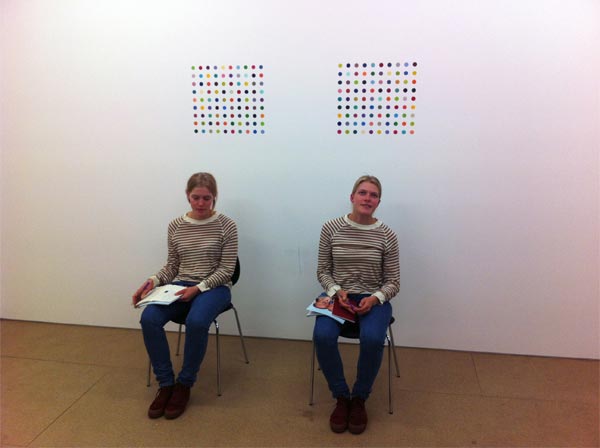

13 Rooms

Xu Zhen

For In Just a Blink of an Eye, 2005

Damien Hirst, 1992

Damien Hirst, 1992

Simon Fujiwara

Future Perfect, 2012

Simon Fujiwara

Future Perfect, 2012

Allora & Calzadilla

Revolving Door, 2011

Clark Beaumont

Coexisting, 2013

Laura Lima

Man=Flesh/Woman=Flesh–Flat, 1997

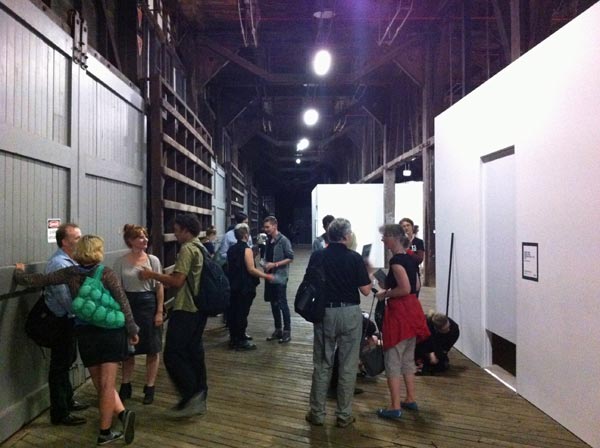

13 Rooms

Curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Klaus Biesenbach

11–21 April 2013

Pier 2/3, Hickson Road, Walsh Bay, Sydney

Difficult world

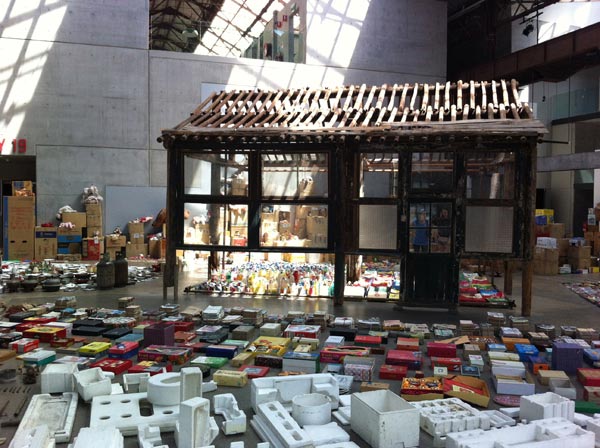

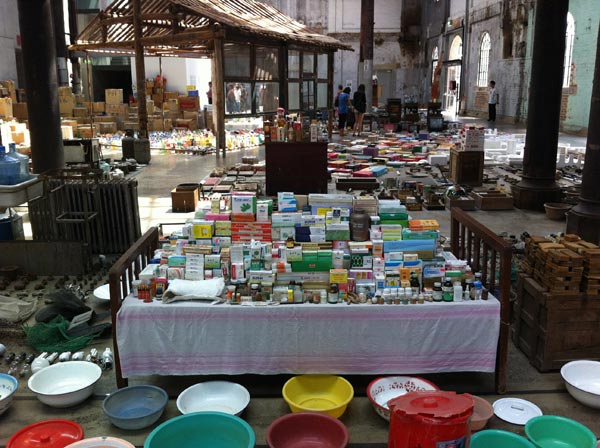

Graeme Smith: Song Dong, Waste Not

Carriageworks with 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art

in association with Sydney Festival: 5 January 5 – 17 March

Published RealTime 113, February March 2013

DIFFICULT WORLD

Although the world can be frightening and frustrating, difficult and dangerous, somehow people quietly find personal ways to engage it, actually cooperate with and make the best of it.

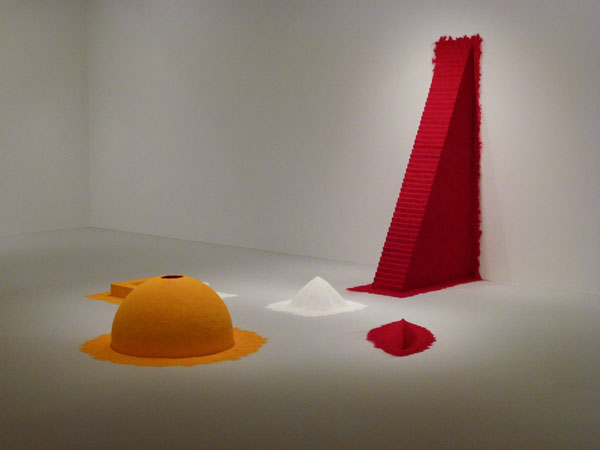

One achingly human example of someone trying to make the best of a difficult world has been made visible—as a vast, walk-through installation on the floor of Carriageworks in Sydney.

Chinese artist Song Dong’s Waste Not is big. But it’s not just the physical extent of the collection that conveys something vaguely melancholic as you walk around it. It’s really (much more than its profuseness) the staggering modesty of those 10,000 objects within it; worn out everyday domestic bits and pieces of a type that most Australians would send, not to St Vincent de Paul, not wholly to the yellow-topped recycle bin, but straight to landfill. Cheap, chipped, patched, scuffed, busted, battered, rusted; folded, sorted, stacked, boxed, bundled, bagged, tied, sacked…but above all, saved. It’s what decades of soul crushing ‘make do’ looks like when you spread it out on a floor—and in this thought there is some sadness.

Waste Not

The exhibition title derives from ‘wu jin qi yong,’ a life-guiding phrase that underscores the traditional Chinese virtue of frugality. According to Song Dong, the dictionary explanation reads, “anything that can somehow be of use, should be used as much as possible. Every resource should be used fully, and nothing should be wasted.”

Song Dong’s Waste Not has, at its conceptual starting point, the hardships of his family, in particular those of his mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, who, in struggling with the shortages and political insecurities of China’s Cultural Revolution, turned to extreme frugality (along with a whole generation of Chinese) to cope and survive. One of the texts in the exhibition written by Zhao Xiangyuan in 2005 recounts in heart-breaking detail the tedious steps she needed to take just to save on soap. She concludes, “I was afraid when my children grew up, they would have to worry about soap rations every month, as I had. I wanted to save the soap until the children got married, then pass these on to them. I never thought they would become useless, because now of course, everyone uses a washing machine. But I couldn’t bear to throw them all out, so I have kept them for a few decades now. Some of that soap is older than Song Dong.”

Song Dong writes, “In that period of insufficiency, this way of thinking and living was a kind of a ‘fabao,’ literally translated as a ‘magic weapon,’ but in times when goods were plenty, the habit of ‘waste not’ became a burden.” “…[M]y mother not only refused to throw away her own things, but wouldn’t allow us to throw anything away either.”

When Zhao Xiangyuan’s husband died in 2002 she had an emotional breakdown, and as her hoarding habit became even more extreme, Song Dong decided to pull her “out of her isolated and grief-stricken world and give her a breath of fresh air…”

Fresh air came in the form of a mother and son collaboration in which the mother became artist and the son, assistant—allowing her to have a “space to put her memories and history in order” by arranging her collection at the beginning of every exhibition. Since Zhao Xiangyuan’s death in 2009, Song Dong’s sister, Song Hui, and wife, Yin Xiuzhen, work with him to reconfigure each new installation.

Rituals of engagement

A human way of trying to cooperate with a difficult world is evident in a commonplace medical disorder.

My understanding (personal, non-medical) of obsessive-compulsive disorder is that it works in a surprisingly real sense as a type of interior magic act. Example: “If I count the steps on this staircase and the number is divisible by three—all will be well, I’ll be safe, ‘it’ won’t happen, I can put my mind at rest and the anxiety on hold.”

The problem is in the repetition. No matter how many times you repeat the ritual—staircase-mathematics, hand-washing, lock-checking, newspaper-hoarding, silently reciting a special incantation, scratching your left ankle five times…whatever your particular routine—the relief from anxiety is fleeting and you never reach that safe place you desperately need to inhabit.

It’s both fascinating and sad to think that, not just an isolated individual, but a whole generation can also be compelled out of desperation to turn to this type of interior ritual, magic weapon, hoarding routine, whatever you prefer to call it—to engage with an uncooperative world.

An introductory panel at the exhibition suggests that Waste Not is both a meditative space for contemplation and self reflection, and a gesture to the richness of family life and memory,” and it did have me doing so: meditating on that richness found in all that patched up, battered and bundled stuff; and also on how Zhao Xiangyuan’s obsessive collecting could be transformed into a more liberating form of ritual—all those reconfigurations of her 10,000 common household objects on gallery floors.

Graeme Smith, RealTime 113

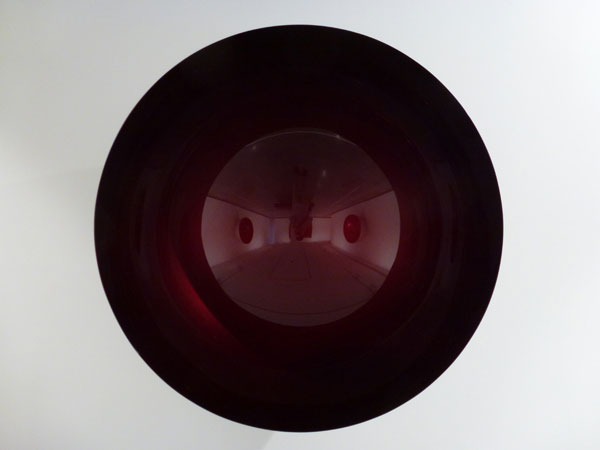

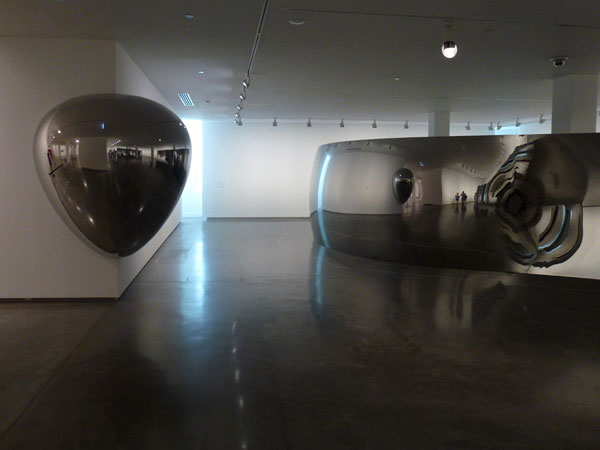

Anish Kapoor in Sydney

Anish Kapoor

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

Sydney International Art Series

x