Ruhe

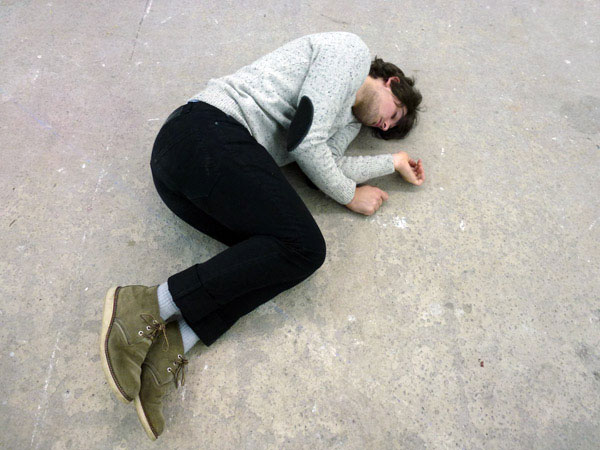

The gallery (standard large white room with concrete floor) gradually fills with people. Many of them know each other (as at all openings). They chat and drink and smoke. There’s a bar and a DJ (it’s a party). A few hours of this. Then a single, sharp, clap-like sound: and some of the partygoers fall down and remain on the floor (frozen, as if sleeping or unconscious) for 10 to 15 minutes. I think it’s all being photographed (or filmed).

Ruhe

A performance by Anouk Kruithof

and location closing party by Autocenter, Berlin

29 September 2012

x

Learning cities

In Germany again for 6 weeks then 1 week in Tokyo.

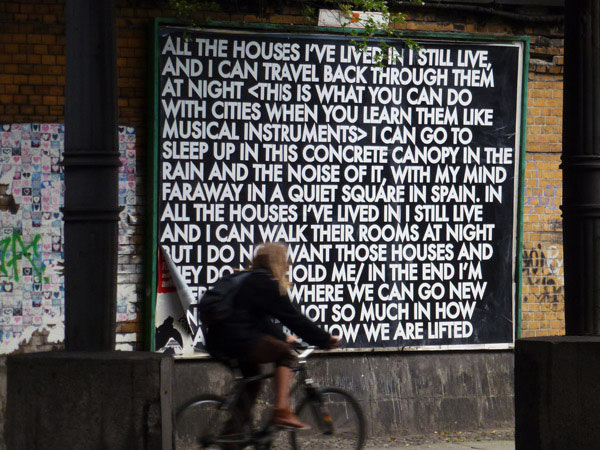

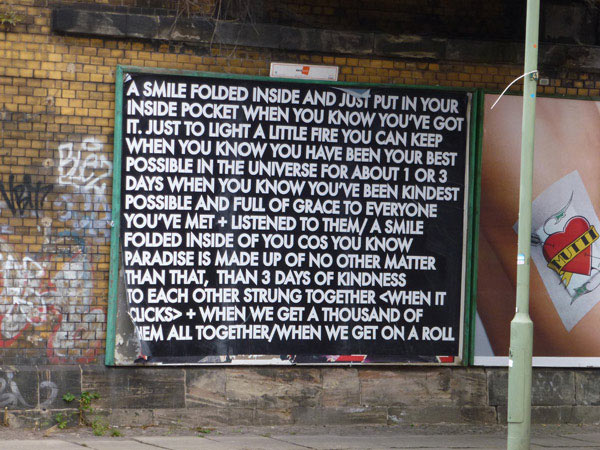

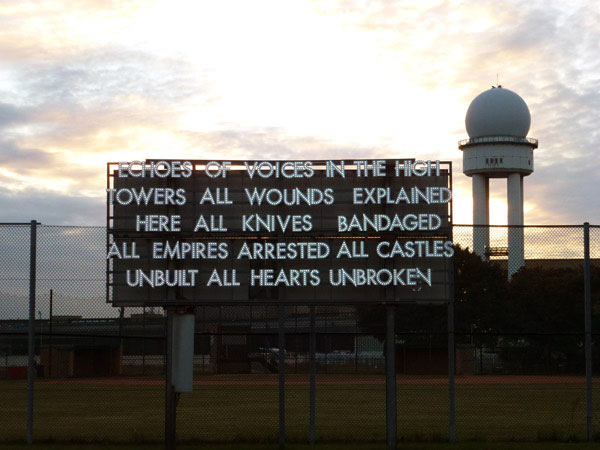

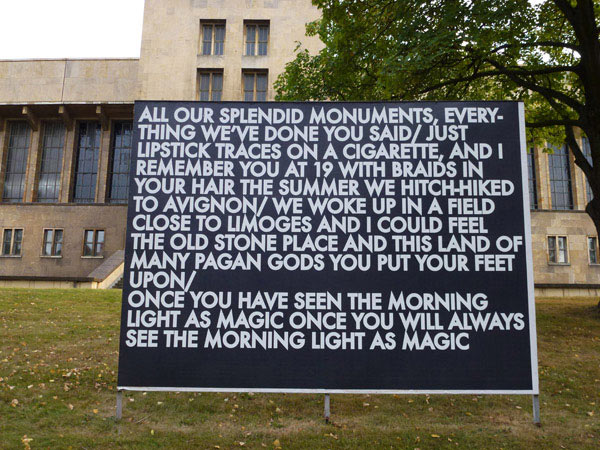

British artist, Robert Montgomery’s installations can be seen in public spaces around Berlin—on billboards and at the former airport, Tempelhof. The posters have been up since July and are looking a bit rough around the edges—but I like that. What isn’t rough around the edges is his language. I like that: a lot.

Robert Montgomery

Echoes of Voices in the High Towers

Presented by Neue Berliner Räume

x

Goodbye Elizabeth

Elizabeth’s father said to her, ‘never go down the same road twice’ — and she didn’t. Elizabeth Mooney: compulsive, gung-ho world traveller; warm-hearted, loveable lefty without a hint of dogma; Cubaphile; official Friend of Fidel; benefactor to hospitals in Havana and the Botanic Gardens in Sydney (she refused to use the word Royal); enthusiastic advocate for Australia becoming a republic (she wanted it to happen in her lifetime); single-minded campaigner for Sydney’s first inhabitants having formal recognition at Bennelong Point; balcony-feeder of the harbour’s rosellas and cockatoos; and provider of many, many dinners and bottles of wine and laughs about the endless parade of nutters that seemed to have passed through our Potts Point building. She helped a lot of people through rough patches (me included) and rarely said a word about it.

In typical Elizabeth style, she phoned me in Germany to pester me into writing an email about what I was up to. I said I would, said goodbye, then typically didn’t get around to it. Maybe I’m imagining it but in hindsight it sounded a bit like a goodbye call.

As I write, it’s around 5.30pm in Sydney and some of Elizabeth’s friends are thinking about opening the champagne. She lived a good life.

Millinery and photography: Wendi Nutt

Rooms 2

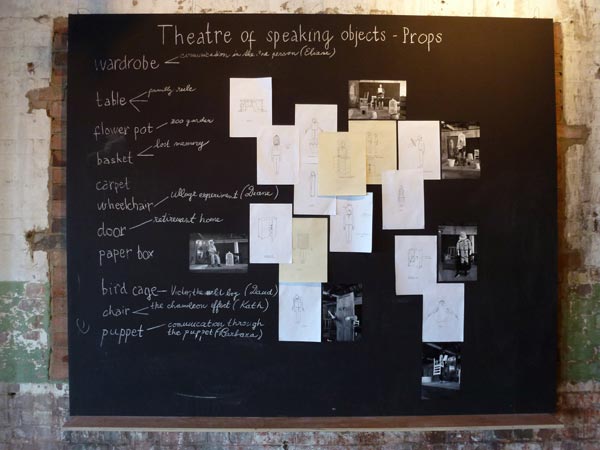

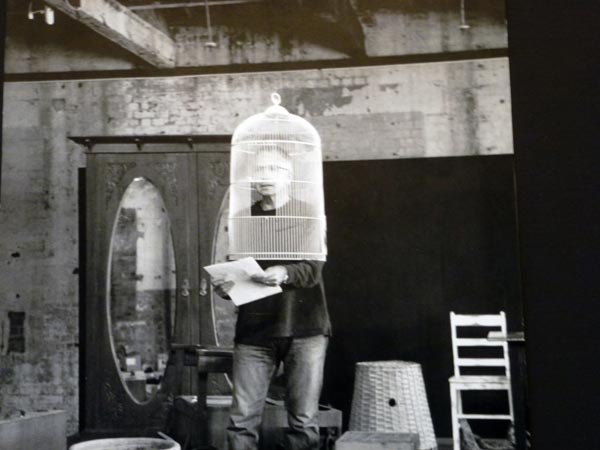

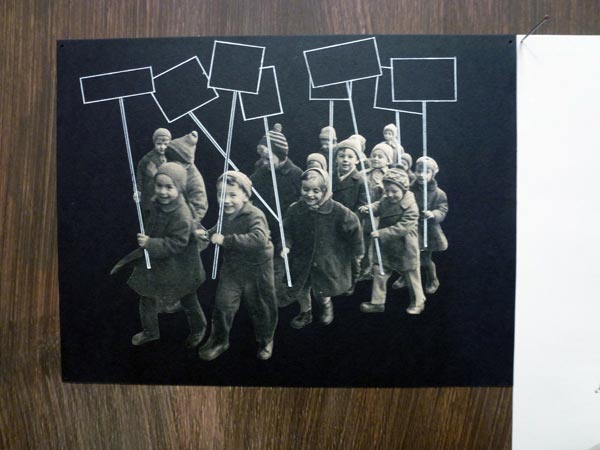

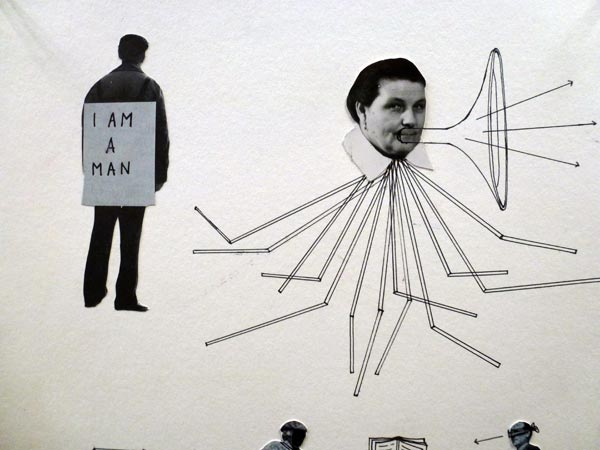

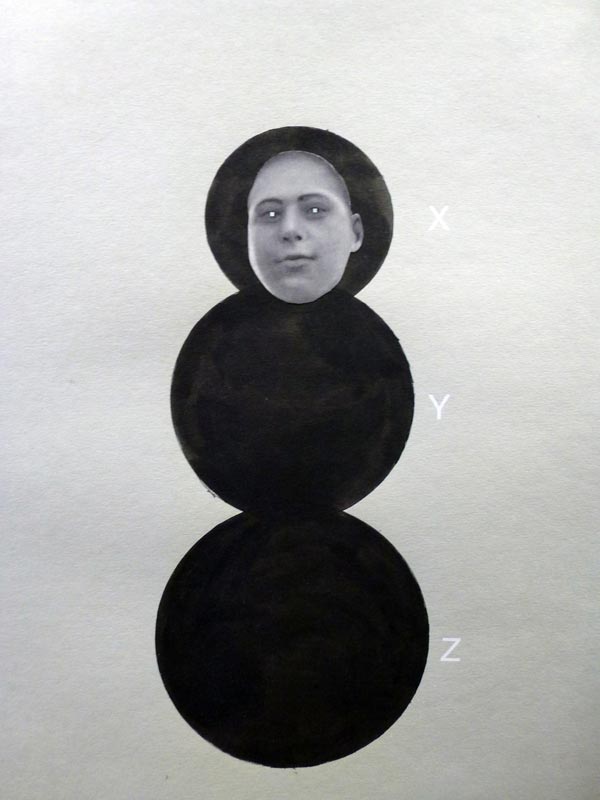

Eva Kotáková

Theatre of Speaking Objects, 2012

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

x

Rooms

Ed Pien with Tanya Tagaq

Source, 2012

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

Bahar Behbahanj and Almagul Menlibayeva

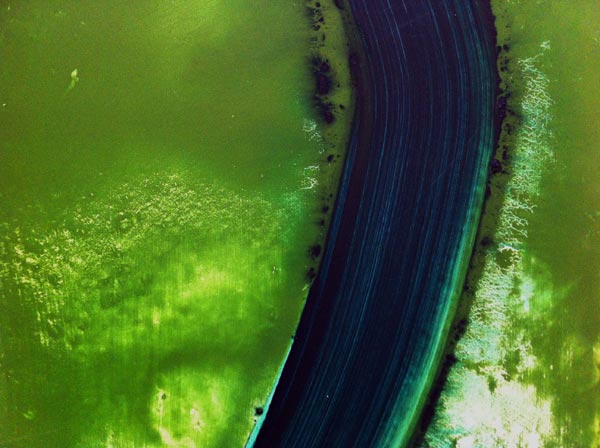

Ride the Caspian, 2011

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

Susan Hefuna

Celebrate Life: I Love Egypt, 2011

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

Susan Hefuna

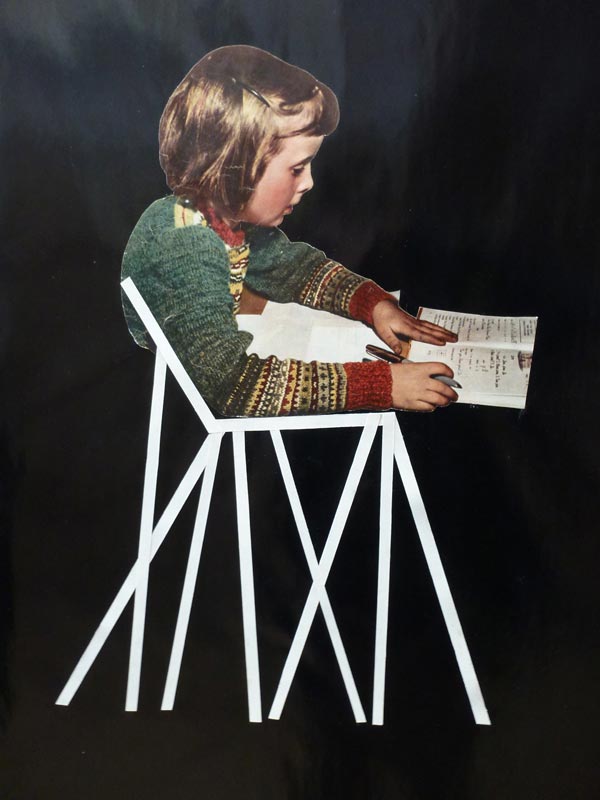

Sriwhana Spong

Learning Duets, 2012

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

Sriwhana Spong

Beach Study, 2012

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

Judith Wright

Desire, 2010

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

Jananne Al-Ani

Shadow sites II, 2011

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

Gao Rong

The static eternity, 2012

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Gao Rong

Jin Shi

Small business karaoke, 2009

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Cake, flora, opera

Café Japone, Randwick, Sydney was playing opera. It seemed just right for their choice of plate.

Hands, flowers, fruit

Hand 1, Edward John Poynter 1836–1919, Helen, 1881

Hand 2, Charles Landelle 1821–1908, Isménie, nymph of Diana, 1878

Flowers, William Buelow Gould 1827–1853, Flowers and fruit, 1849

Fruit, John Everett Millais 1829–1896, The captive, 1882

x

In praise of Tanizaki, sort of

1, the Spanish Club

2, Stitch bar

3, State Theatre

4, Shady Pines bar

x

Please disturb

Graeme Smith: Thomas Demand, The Dailies, with contributions by Louis Begley and Miuccia Prada, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Commercial Travellers’ Association (CTA), MLC Centre, Martin Place, Sydney, March 23-April 22.

For better exhibition photography than mine please visit RealTime 109, June 2012.

Observation

When Sydney people walk into an unfamiliar room the first thing they do is head for the window. Everything—including the art on the walls—is sized up only after a quick assessment of the quality of the view. Sydney is a view city—even beyond white yachts bobbing on a sparkling harbour.

The ‘Rear Window’ effect of looking into the rooms of others, the lovely mute blankness of windowless brick, a neighbour’s frangipani or the shiny seduction of a retail strip all make good views, as they would in other cities, but in Sydney it’s more important. The view reigns. Sydney seems to look outwards; looking inwards is inappropriate behaviour. Disturbing. As is randomly opening the door to a hotel room you haven’t booked.

The Commercial Travellers’ Association houses a little-known, little hotel—a mid-70s Harry Seidler designed concrete mushroom in the centre of Sydney’s financial district. On one of the above ground floors, 16 little bedrooms look out radially onto the high-end retail and grand bank facades of Castlereagh Street and Martin Place. This was the setting for German artist Thomas Demand’s, The Dailies, and where a polite attendant in black invited me to start anywhere—so I opened the door to room 413 and went to the window.

Through the window

Prada, in an Art Deco building, Martin Place.

On the wall

A photograph of a window in a brown wall. The window has a cheap-looking venetian blind covering it. The lower third of the slats is dishevelled—a word normally used for hair or clothing that also works for mussed up venetians. The ceiling is standard office-commercial. Cheap. Utilitarian. All of the above is meticulously constructed from paper, photographed, then beautifully and expensively printed using an almost obsolete process called dye transfer, by Thomas Demand. The result is a slickly real image that doesn’t quite add up.

On the dresser

A tiny electric jug (everything is tiny in these rooms), a little telephone, a small bottle of wine, one glass, a laminated sheet of house information that ends predictably with…

“THIS IS A NON SMOKING ROOM

THANK YOU’

and laminated in the same hotel-room manner, a story fragment by American novelist Louis Begley…

“THE WHITE CORRIDOR WHEN

THEY ARRIVED AT

GREGOR’S FLOOR

MAKES HIM THINK OF A HOSPITAL.

HE TELLS THAT TO LENI.

She explodes in laughter and explains

how on every floor the corridor circles the building.

On some floors there are only double rooms.

This is the floor of singles.”

In the air

A fragrance designed or specified (not sure) by Miuccia Prada.

The Dailies

One circular floor, level four. Sixteen rooms. Fifteen, each with a photograph, a fragrance, a view and a fragment of story about Gregor the commercial traveller and Leni the receptionist. One room is locked, a red swing tag on the handle reading, “Please do not disturb.”

Begin

Turn the handle and push against one of the tightly sprung doors; so tightly sprung that it feels locked, until the attendant in black tells you to push a bit harder. A touch of guilt about randomly barging into a hotel room that isn’t yours, then a hint of relief in discovering that no one is there. The lunchtime city outside is soundless through the double glazing. The only sound in the room is the humming of the air conditioner through the grate in the bulkhead, sounding for a moment like a shower running in the room next door. Look at the photograph on the wall above the bed. Read the text on the dresser. Look out the window. Step back (not far in this tiny room) and frame all three—the picture, the dresser with the text, the window—in your field of vision. Turn back to the door. Turn the handle, open, realise it’s the door for the bathroom, and a slight sense of disorientation sets in.

Few of us miss this point, that regardless of where you are in the world, these mean little hotel rooms, apart from all looking the same, have one other thing in common: they’re non-places. Places between other places. In The Dailies, Demand’s photographs pick up on this and push the fourth floor into another level of disengagement.

Loaded emptiness

Demand has described his subjects as simply places you pass by, things that are formally interesting (no more than that), revisited memories fixed in photography or the nuclei of narratives. The refreshingly non-interpretive John Kaldor calls them little observations in the city, and this is essentially what they are. But it’s the effect of moving through the gaps, being in-between these little stories, that draws you in to another, less worldly place. A description I once heard used for the loaded emptinesses of Berlin comes to mind and seems to fit the feeling perfectly: ghostly present absences; and picking up on the theme I did find myself doing this door-to-door visitation a bit like a commercial travelling wraith. Cut off, removed, silenced, disconnected—but at the same time hoping that the group of jabbering school kids I saw earlier had finally pissed off and left me to wander alone—to be trapped in the gaps between someone else’s story, each door opening to reveal just a sampling of what wasn’t there.

Give and take

Begley was delightful. His words played with me—and the building, and Sydney, and Australia, and readers, and Kafka, and airports, and commercial travellers and lousy little hotel rooms. Regretfully, Prada’s fragrances didn’t do a thing—but only because of the limiting effects of asthma and a cold. On the other hand, Thomas Demand seemed to be provoking a type of reflection, and presumably insight, that only comes about through displacement. Demand gives, prescribing the vision, as he says, and Demand takes, handing you the moment and at the same time cutting it away. The subject in the photograph is a construction. It has an aura of reality but at the same time it doesn’t add up. It’s the slightly disturbing, preternatural silence of the spaces that exist either side of these disconnected moments that I find overwhelmingly seductive.

Graeme Smith, RealTime 109, June July 2012