Difficult world

Graeme Smith: Song Dong, Waste Not

Carriageworks with 4A Centre for Contemporary Asian Art

in association with Sydney Festival: 5 January 5 – 17 March

Published RealTime 113, February March 2013

DIFFICULT WORLD

Although the world can be frightening and frustrating, difficult and dangerous, somehow people quietly find personal ways to engage it, actually cooperate with and make the best of it.

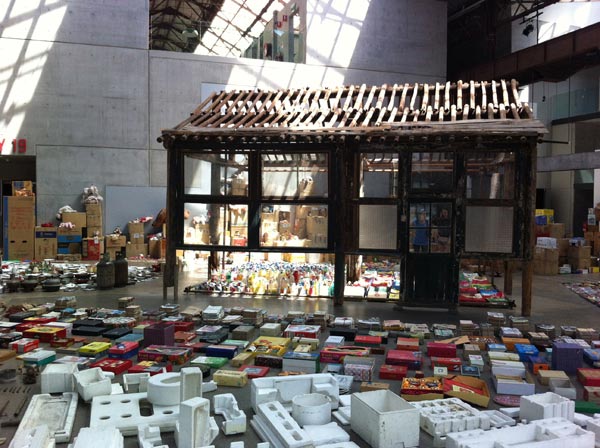

One achingly human example of someone trying to make the best of a difficult world has been made visible—as a vast, walk-through installation on the floor of Carriageworks in Sydney.

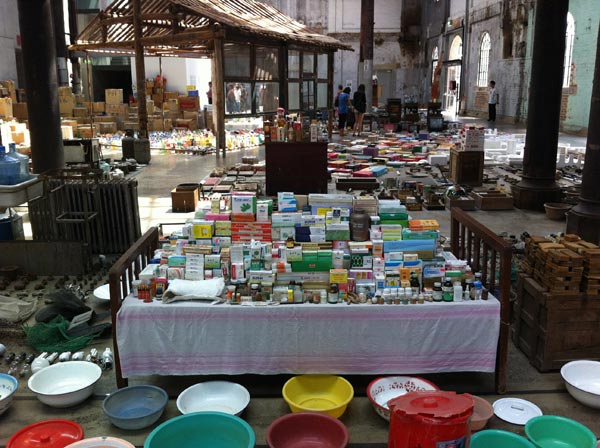

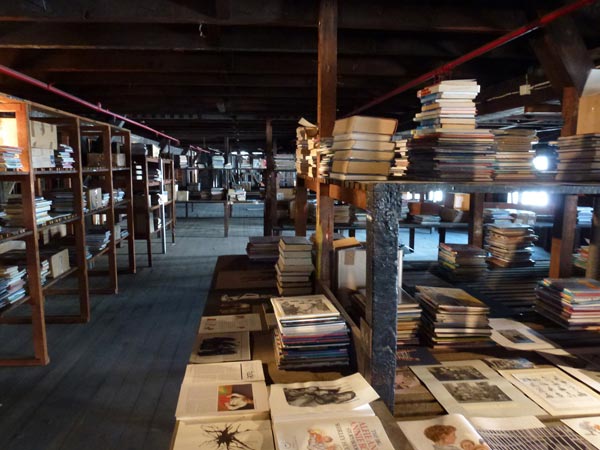

Chinese artist Song Dong’s Waste Not is big. But it’s not just the physical extent of the collection that conveys something vaguely melancholic as you walk around it. It’s really (much more than its profuseness) the staggering modesty of those 10,000 objects within it; worn out everyday domestic bits and pieces of a type that most Australians would send, not to St Vincent de Paul, not wholly to the yellow-topped recycle bin, but straight to landfill. Cheap, chipped, patched, scuffed, busted, battered, rusted; folded, sorted, stacked, boxed, bundled, bagged, tied, sacked…but above all, saved. It’s what decades of soul crushing ‘make do’ looks like when you spread it out on a floor—and in this thought there is some sadness.

Waste Not

The exhibition title derives from ‘wu jin qi yong,’ a life-guiding phrase that underscores the traditional Chinese virtue of frugality. According to Song Dong, the dictionary explanation reads, “anything that can somehow be of use, should be used as much as possible. Every resource should be used fully, and nothing should be wasted.”

Song Dong’s Waste Not has, at its conceptual starting point, the hardships of his family, in particular those of his mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, who, in struggling with the shortages and political insecurities of China’s Cultural Revolution, turned to extreme frugality (along with a whole generation of Chinese) to cope and survive. One of the texts in the exhibition written by Zhao Xiangyuan in 2005 recounts in heart-breaking detail the tedious steps she needed to take just to save on soap. She concludes, “I was afraid when my children grew up, they would have to worry about soap rations every month, as I had. I wanted to save the soap until the children got married, then pass these on to them. I never thought they would become useless, because now of course, everyone uses a washing machine. But I couldn’t bear to throw them all out, so I have kept them for a few decades now. Some of that soap is older than Song Dong.”

Song Dong writes, “In that period of insufficiency, this way of thinking and living was a kind of a ‘fabao,’ literally translated as a ‘magic weapon,’ but in times when goods were plenty, the habit of ‘waste not’ became a burden.” “…[M]y mother not only refused to throw away her own things, but wouldn’t allow us to throw anything away either.”

When Zhao Xiangyuan’s husband died in 2002 she had an emotional breakdown, and as her hoarding habit became even more extreme, Song Dong decided to pull her “out of her isolated and grief-stricken world and give her a breath of fresh air…”

Fresh air came in the form of a mother and son collaboration in which the mother became artist and the son, assistant—allowing her to have a “space to put her memories and history in order” by arranging her collection at the beginning of every exhibition. Since Zhao Xiangyuan’s death in 2009, Song Dong’s sister, Song Hui, and wife, Yin Xiuzhen, work with him to reconfigure each new installation.

Rituals of engagement

A human way of trying to cooperate with a difficult world is evident in a commonplace medical disorder.

My understanding (personal, non-medical) of obsessive-compulsive disorder is that it works in a surprisingly real sense as a type of interior magic act. Example: “If I count the steps on this staircase and the number is divisible by three—all will be well, I’ll be safe, ‘it’ won’t happen, I can put my mind at rest and the anxiety on hold.”

The problem is in the repetition. No matter how many times you repeat the ritual—staircase-mathematics, hand-washing, lock-checking, newspaper-hoarding, silently reciting a special incantation, scratching your left ankle five times…whatever your particular routine—the relief from anxiety is fleeting and you never reach that safe place you desperately need to inhabit.

It’s both fascinating and sad to think that, not just an isolated individual, but a whole generation can also be compelled out of desperation to turn to this type of interior ritual, magic weapon, hoarding routine, whatever you prefer to call it—to engage with an uncooperative world.

An introductory panel at the exhibition suggests that Waste Not is both a meditative space for contemplation and self reflection, and a gesture to the richness of family life and memory,” and it did have me doing so: meditating on that richness found in all that patched up, battered and bundled stuff; and also on how Zhao Xiangyuan’s obsessive collecting could be transformed into a more liberating form of ritual—all those reconfigurations of her 10,000 common household objects on gallery floors.

Graeme Smith, RealTime 113

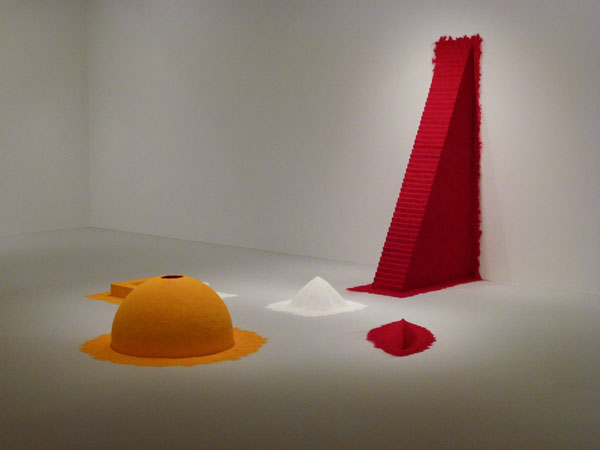

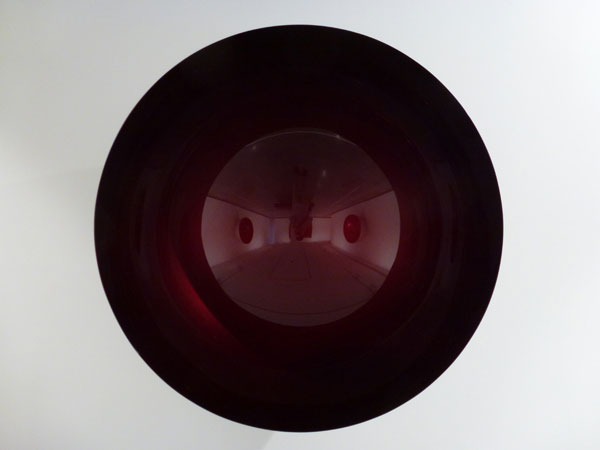

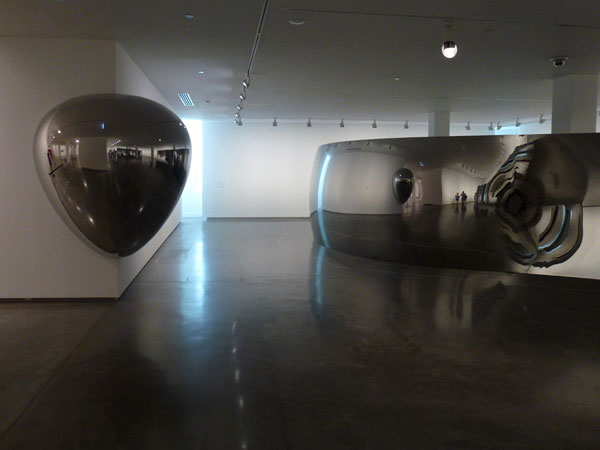

Anish Kapoor in Sydney

Anish Kapoor

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

Sydney International Art Series

x

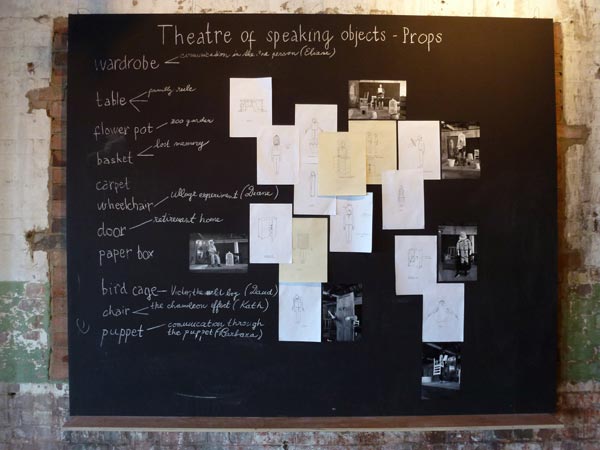

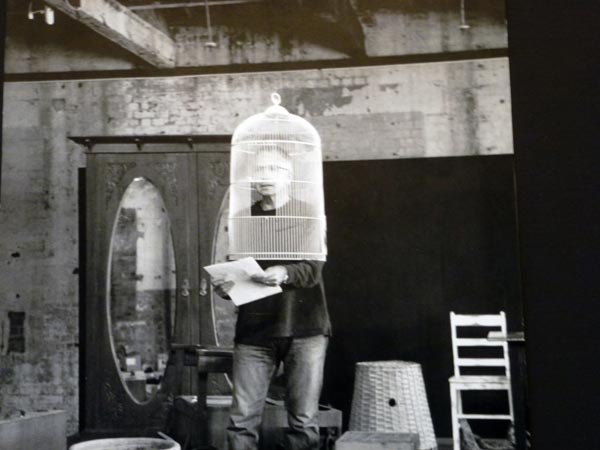

Rooms 2

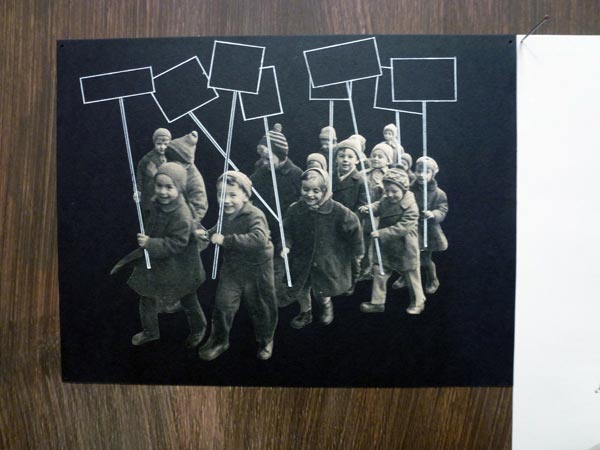

Eva Kotáková

Theatre of Speaking Objects, 2012

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

x

Rooms

Ed Pien with Tanya Tagaq

Source, 2012

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

Bahar Behbahanj and Almagul Menlibayeva

Ride the Caspian, 2011

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

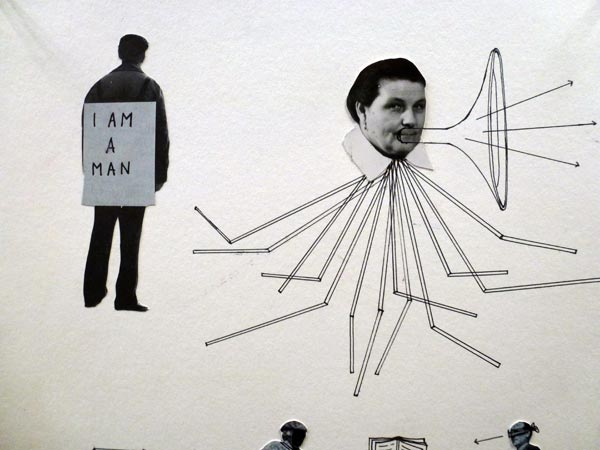

Susan Hefuna

Celebrate Life: I Love Egypt, 2011

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

Susan Hefuna

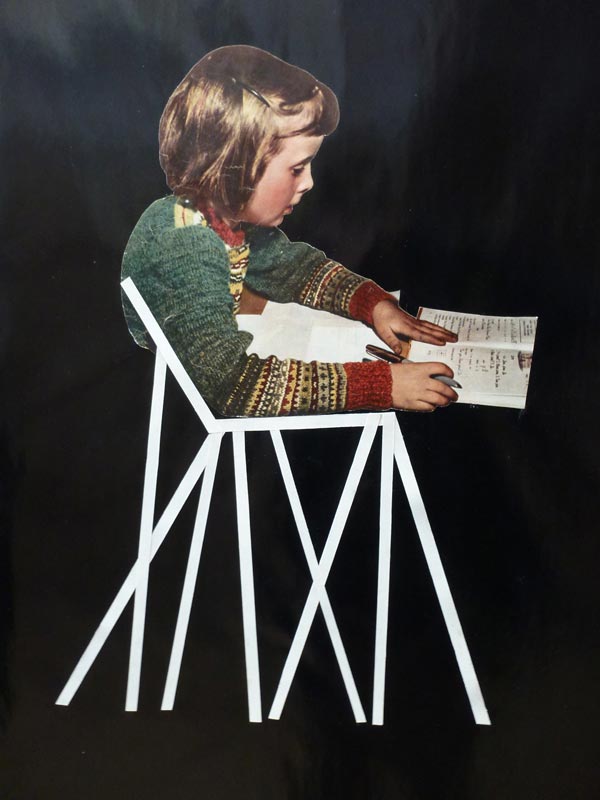

Sriwhana Spong

Learning Duets, 2012

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

Sriwhana Spong

Beach Study, 2012

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

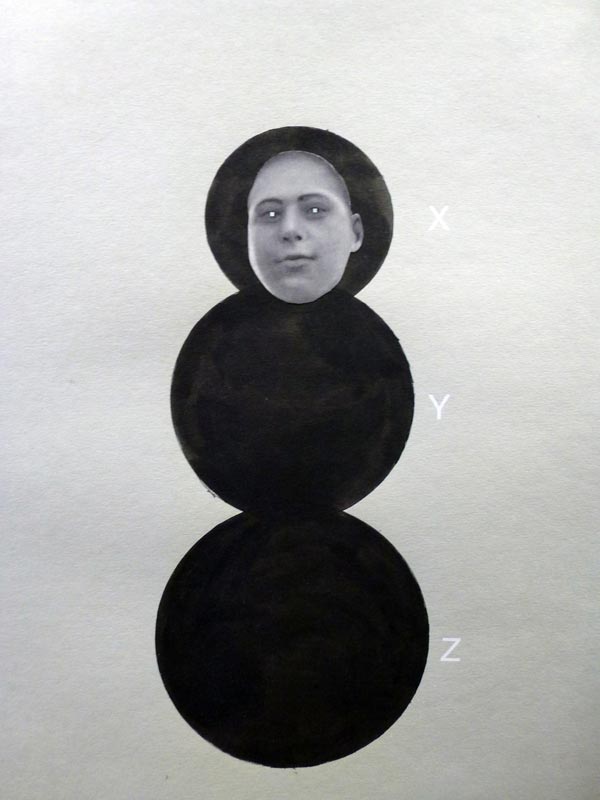

Judith Wright

Desire, 2010

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

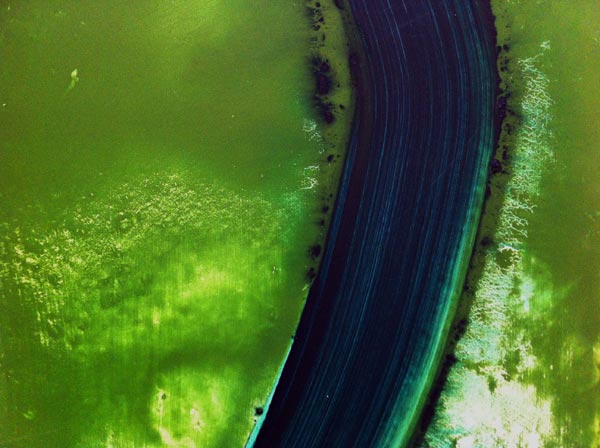

Jananne Al-Ani

Shadow sites II, 2011

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Cockatoo Island

Gao Rong

The static eternity, 2012

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Gao Rong

Jin Shi

Small business karaoke, 2009

18th Biennale of Sydney 2012, Art Gallery of New South Wales

Cake, flora, opera

Café Japone, Randwick, Sydney was playing opera. It seemed just right for their choice of plate.

Hands, flowers, fruit

Hand 1, Edward John Poynter 1836–1919, Helen, 1881

Hand 2, Charles Landelle 1821–1908, Isménie, nymph of Diana, 1878

Flowers, William Buelow Gould 1827–1853, Flowers and fruit, 1849

Fruit, John Everett Millais 1829–1896, The captive, 1882

x

In praise of Tanizaki, sort of

1, the Spanish Club

2, Stitch bar

3, State Theatre

4, Shady Pines bar

x

Please disturb

Graeme Smith: Thomas Demand, The Dailies, with contributions by Louis Begley and Miuccia Prada, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Commercial Travellers’ Association (CTA), MLC Centre, Martin Place, Sydney, March 23-April 22.

For better exhibition photography than mine please visit RealTime 109, June 2012.

Observation

When Sydney people walk into an unfamiliar room the first thing they do is head for the window. Everything—including the art on the walls—is sized up only after a quick assessment of the quality of the view. Sydney is a view city—even beyond white yachts bobbing on a sparkling harbour.

The ‘Rear Window’ effect of looking into the rooms of others, the lovely mute blankness of windowless brick, a neighbour’s frangipani or the shiny seduction of a retail strip all make good views, as they would in other cities, but in Sydney it’s more important. The view reigns. Sydney seems to look outwards; looking inwards is inappropriate behaviour. Disturbing. As is randomly opening the door to a hotel room you haven’t booked.

The Commercial Travellers’ Association houses a little-known, little hotel—a mid-70s Harry Seidler designed concrete mushroom in the centre of Sydney’s financial district. On one of the above ground floors, 16 little bedrooms look out radially onto the high-end retail and grand bank facades of Castlereagh Street and Martin Place. This was the setting for German artist Thomas Demand’s, The Dailies, and where a polite attendant in black invited me to start anywhere—so I opened the door to room 413 and went to the window.

Through the window

Prada, in an Art Deco building, Martin Place.

On the wall

A photograph of a window in a brown wall. The window has a cheap-looking venetian blind covering it. The lower third of the slats is dishevelled—a word normally used for hair or clothing that also works for mussed up venetians. The ceiling is standard office-commercial. Cheap. Utilitarian. All of the above is meticulously constructed from paper, photographed, then beautifully and expensively printed using an almost obsolete process called dye transfer, by Thomas Demand. The result is a slickly real image that doesn’t quite add up.

On the dresser

A tiny electric jug (everything is tiny in these rooms), a little telephone, a small bottle of wine, one glass, a laminated sheet of house information that ends predictably with…

“THIS IS A NON SMOKING ROOM

THANK YOU’

and laminated in the same hotel-room manner, a story fragment by American novelist Louis Begley…

“THE WHITE CORRIDOR WHEN

THEY ARRIVED AT

GREGOR’S FLOOR

MAKES HIM THINK OF A HOSPITAL.

HE TELLS THAT TO LENI.

She explodes in laughter and explains

how on every floor the corridor circles the building.

On some floors there are only double rooms.

This is the floor of singles.”

In the air

A fragrance designed or specified (not sure) by Miuccia Prada.

The Dailies

One circular floor, level four. Sixteen rooms. Fifteen, each with a photograph, a fragrance, a view and a fragment of story about Gregor the commercial traveller and Leni the receptionist. One room is locked, a red swing tag on the handle reading, “Please do not disturb.”

Begin

Turn the handle and push against one of the tightly sprung doors; so tightly sprung that it feels locked, until the attendant in black tells you to push a bit harder. A touch of guilt about randomly barging into a hotel room that isn’t yours, then a hint of relief in discovering that no one is there. The lunchtime city outside is soundless through the double glazing. The only sound in the room is the humming of the air conditioner through the grate in the bulkhead, sounding for a moment like a shower running in the room next door. Look at the photograph on the wall above the bed. Read the text on the dresser. Look out the window. Step back (not far in this tiny room) and frame all three—the picture, the dresser with the text, the window—in your field of vision. Turn back to the door. Turn the handle, open, realise it’s the door for the bathroom, and a slight sense of disorientation sets in.

Few of us miss this point, that regardless of where you are in the world, these mean little hotel rooms, apart from all looking the same, have one other thing in common: they’re non-places. Places between other places. In The Dailies, Demand’s photographs pick up on this and push the fourth floor into another level of disengagement.

Loaded emptiness

Demand has described his subjects as simply places you pass by, things that are formally interesting (no more than that), revisited memories fixed in photography or the nuclei of narratives. The refreshingly non-interpretive John Kaldor calls them little observations in the city, and this is essentially what they are. But it’s the effect of moving through the gaps, being in-between these little stories, that draws you in to another, less worldly place. A description I once heard used for the loaded emptinesses of Berlin comes to mind and seems to fit the feeling perfectly: ghostly present absences; and picking up on the theme I did find myself doing this door-to-door visitation a bit like a commercial travelling wraith. Cut off, removed, silenced, disconnected—but at the same time hoping that the group of jabbering school kids I saw earlier had finally pissed off and left me to wander alone—to be trapped in the gaps between someone else’s story, each door opening to reveal just a sampling of what wasn’t there.

Give and take

Begley was delightful. His words played with me—and the building, and Sydney, and Australia, and readers, and Kafka, and airports, and commercial travellers and lousy little hotel rooms. Regretfully, Prada’s fragrances didn’t do a thing—but only because of the limiting effects of asthma and a cold. On the other hand, Thomas Demand seemed to be provoking a type of reflection, and presumably insight, that only comes about through displacement. Demand gives, prescribing the vision, as he says, and Demand takes, handing you the moment and at the same time cutting it away. The subject in the photograph is a construction. It has an aura of reality but at the same time it doesn’t add up. It’s the slightly disturbing, preternatural silence of the spaces that exist either side of these disconnected moments that I find overwhelmingly seductive.

Graeme Smith, RealTime 109, June July 2012