January 2017

Gates

A couple of (quite a lot of) gates I pass or sometimes go through every day. I like pretty much everything about them: their simplicity, elegance, function, post-fixings, colour, history, reliability, resilience, individuality, the need to find a rock or a stick or a bump in the ground to hold them open when you’re driving solo, not having to find a rock when you have a passenger, the way they punctuate fence lines.

A couple of (quite a lot of) gates I pass or sometimes go through every day. I like pretty much everything about them: their simplicity, elegance, function, post-fixings, colour, history, reliability, resilience, individuality, the need to find a rock or a stick or a bump in the ground to hold them open when you’re driving solo, not having to find a rock when you have a passenger, the way they punctuate fence lines.

The Other Life of Objects

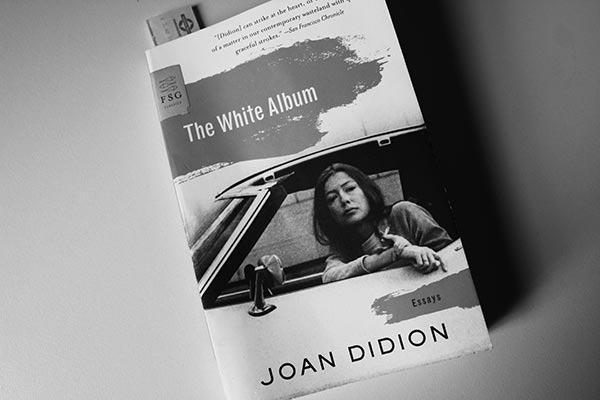

I have just finished reading The White Album — a book of mainly 70s essays by the US writer Joan Didion — and I’m feeling inadequate, or more to the point, pointless. Didion seems to get to her own point by the sparest means, and with language that is, as The New York Times Book Review says, “subtly musical in its phrasing and exact”.

In one essay, At the Dam, she recounts a second visit to the Hoover Dam where her guide from the Bureau of Reclamation invites her to touch one of the turbines.

We watched a hundred-ton steel shaft plunging down to that place where the water was. And finally we got down to that place where the water was, where the water sucked out of Lake Mead roared through thirty-foot penstocks and then into thirteen-foot penstocks and finally into the turbines themselves. “Touch it,” the Reclamation said, and I did, and for a long time I just stood there with my hands on the turbine. It was a peculiar moment, but so explicit as to suggest nothing beyond itself.*

Didion became fixated on the idea of the dam after her first visit in 1967, seeing images of its concrete face and transmission towers, spillways and tailraces through her inner eye in the most unlikely places, and wondering why the place was so affecting. Affecting, beyond the usual emotions that these vast monuments to achievement and lost lives have provoked; that have led to stock phrases (they made the desert bloom) or heroic artworks (bronzes of muscular citizens clutching sheaves of wheat). On the second visit the Reclamation man explains a marble star map, then afterwards, out in the desert towards sunset, Didion begins to understand the cause of her fixation.

I walked across the marble star map that traces a sidereal revolution of the equinox and fixes forever, the Reclamation man told me, for all time and for all people who can read the stars, the date the dam was dedicated. The star map was, he had said, for when we were all gone and the dam was left. I had not thought much of it when he had said it, but I thought of it then, with the wind whining and the sun dropping behind a mesa with the finality of a sunset in space. Of course that was the image I had seen always, seen it without quite realising what I saw, a dynamo finally free of man, splendid at last in its absolute isolation, transmitting power and releasing water to a world where no one is.

It is possible but not always easy to sense this other life of objects; a condition of things that is beyond metaphor and message, and in peculiar moments — perhaps as a type of disengagement with their accretions of meaning — sense them as things at least partly free of human points of reference and symbolism. Can objects be disinterpreted? I think never. Only by the annihilation of the thinkers. The object needs our absence to bring its other life to fullness.

Didion’s massive, roaring dynamo, still transmitting power and releasing water to a world empty of humans is a thought, in its vastness and finality, sublime. In the absence of people this thing will become nameless, unthought of, unthinkable, and finally being (no longer suggesting) nothing beyond itself.

Notes

Joan Didion *

The White Album

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009

Essay: The Dam, 1970

The Other Life of Objects is taken from Undefinable Places In-between — a series of short essays I have written and continue to write under that title.

No Runtime

What we think of as the present, is no more than that: a thought, an idea; or a formless, timeless, undefinable, unfixed, unfilled state of in-betweenness. A point of transition. A flick-switch between past and future.

It may seem like a small movie—each spectral frame a memory from the immediate past or an imagining for the immediate future, providing an illusion of sequential time passing, but the present has no start, no finish, no runtime. The runtime version of the present is an imaginary construction; a narrative, because memory is a narrative — a visit to the past through imagination — not a recording, not a movie.

The present contains no story. Nothing happens in the present because there is no ‘in’. The present can only be inadequately placed through stories that will never fit: the present is me pouring a cup of tea: the present is a glimpse of a red letterbox as I turn a corner in the street. All of these perceptions of the present are really constructions through which the instant of the present has been extended by adding a past and future to either side of the point of transition.

As elusive as the present may be, there are instances when this point of unfilled in-betweenness may be experienced in itself — or for itself. Suddenly you’re not looking at the movie. You’re inside the experience and outside time. The present is still a point of transition —no longer, however, between past and future, but between a viewer and an image, a listener and a piece of music, a stroller and a landscape, a reader and a text.

A haiku can do this: pluck the reader from the flow of time and dissolve this narrative view of the present. This is a point of stillness where past and future fall away, narrative time disappears, the reader and the words vanish, and there is only the present — an in-between place of absolute nowness.

Notes

Picture: If We Never Meet Again,

Two channel video, Noam Toran, (2010).

No Runtime is taken from Undefinable Places In-between — a series of short essays I have written and continue to write under that title.

Right to Shop

There are many explanations for why we shop. That is, shopping for reasons beyond satisfying fundamental requirements like the need stay out of the rain or postpone death by eating.

In the better funded phases of my life I often took comfort from this one: I shop because it’s something I can get right.

Over one lifetime we take on all manner of tasks. We try to be more attractive to certain people, we go through agonies of self doubt, begin countless dead-end ventures, fret about our careers, become anxious about what we think we can and can’t achieve—and we often fail.

But shopping is easy. All it takes is desire and money. So long as we have the wish and the wherewithal we can achieve success—guaranteed—in minutes or seconds. No brick walls. No self doubt or agonising over consequences or worrying whether or not we have the talent or genetic raw material for it.

It is difficult to fail when shopping.

Notes

“It’s a hard place to run in to for a pair of stockings,” a friend complained to me recently of Ala Moana, and I knew that she was not yet ready to surrender her ego to the idea of the center. The last time I went to Ala Moana it was to buy The New York Times. Because The New York Times was not in, I sat on the mall for a while and ate caramel corn. In the end I bought not The New York Times at all but two straw hats at Liberty House, four bottles of nail enamel at Woolworth’s, and a toaster, on sale at Sears. In the literature of shopping centers these would be described as impulse purchases, but the impulse here was obscure. I do not wear hats, nor do I like caramel corn. I do not use nail enamel. Yet flying back across the Pacific I regretted only the toaster.

Joan Didion,

On the Mall, 1975.

Picture: Westfield, Sydney.

Photo: GS

Right to Shop is taken from Undefinable Places In-between — a series of short essays I have written and continue to write under that title.

All is Rosy

Commercial messages work on us on various levels.

Regarding one level, we have grown up with advertising and we understand that rosy claims are crafted by people who get paid for it—whether they believe it or not. The rosy claim is a given. People understand the idea of shades of truth and truths (or lies) in context.

On another level, on some mysterious other-plane of consciousness, the rosy claim is assimilated and believed. There is a belief that the purchase will magically change our lives.

Of course the magic can be explained away as messages that appeal to deep needs and fears—the need to be loved or found attractive, the need to at least appear to be successful, the need to fulfil powerful obligations, the need to be part of something greater—but there is also an element operating here that is more aligned to a type of enchantment than psychological drives.

One presumes that if enchantment is happening then some type of entity is doing the enchanting — casting the spell. But it is not just the advertiser, or an ad agency creative team or a marketing strategist or a brand influencing blogger who creates the allure through well crafted messages and imagery, but also the products themselves. Even if the spin were somehow subtracted from the equation, the shiny car, the artfully prepared restaurant meal, the jacket, the jeans, the table, the chair, the kitchen blender, radiate some type of primal, fetishistic “come hither” that goes beyond being an aid to self image.

The enchantment can also be explained away as effective product design: the curves and colours, textures, weight, whatever—that makes a thing with a price tag sexy or must-have. The entity creating the enchantment could be, say, an industrial designer, or a product designer or a fashion designer. But this still doesn’t completely account for the allure. This type of product design is also part of the marketing message; the spin.

Something even beyond all of this is operating here.

With the same innocence and sense of wonder as a small kid holding up a string of plastic rubies to the sky and being charmed by the way the pink and crimson light is refracted so beautifully through its facets, we look at the car or the chair or the blender and we “get it”; that what we now have is a talisman with the transformative power to renew life—not by driving it or sitting on it or blending with it or looking at it or showing it to the world but merely by having it in our presence.

Back home from a day’s spending at the shopping precinct, you take the new jacket; drape it over the sofa. Place the new shoes nearby, still in the unlidded box with its crisp tissue paper. Next to the box, an exquisitely designed perfume bottle. Stand back and admire the arrangement. The coat. The shoes. The perfume. It looks like a magazine shoot. Sure. What you see is going to make you look more attractive and successful; and they are, in themselves, beautiful objects; but something else is happening. All three items are beaming their magic into some unfathomable place in your soul.

How else could we juggle the two states of mind simultaneously? Not believing and believing at the same time.

Notes

Picture: Watch advertisement.

Photo: GS.

All is Rosy is taken from Undefinable Places In-between — a series of short essays I have written and continue to write under that title.